More actions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Main|Economic |

{{Main|Economic systems}} |

||

<h3>Introduction</h3> |

<h3>Introduction</h3> |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

Price stability is normally obtained by controlling the growth in the amount of money to correspond to growth in economic output (ie GDP). If economic output grows by 2% then the amount of money can increase by 2% without inflation. Another way to put this is that if the central bank lends an investor, say $100 million, by “printing” the funds into existence, and that investor then creates $100 million of new goods that people actually buy, then no inflation has been created. If the investor fails to create any new goods then that $100 million simply causes prices to increase. It is like giving consumers a free money gift, totaling $100 million, to spend into the current economy. That increased money will cause inflation. |

Price stability is normally obtained by controlling the growth in the amount of money to correspond to growth in economic output (ie GDP). If economic output grows by 2% then the amount of money can increase by 2% without inflation. Another way to put this is that if the central bank lends an investor, say $100 million, by “printing” the funds into existence, and that investor then creates $100 million of new goods that people actually buy, then no inflation has been created. If the investor fails to create any new goods then that $100 million simply causes prices to increase. It is like giving consumers a free money gift, totaling $100 million, to spend into the current economy. That increased money will cause inflation. |

||

It is important to understand one central feature of modern [[Economic |

It is important to understand one central feature of modern [[Economic systems|economic systems]]: they create the money first, out of thin air so to speak. Then they hope the money is well spent (or rather, invested). Many people see this is an unfortunate consequence of fiat money but it is really part of the design. If every project we wanted to do had to find existing money to do it with, our economy would be in for a massive slowdown, and no doubt several years of contraction while the new system is adjusted to. Once we settled down we’d have to get used to very slow economic growth thenceforward. Modern economies operate by decreeing the money into existence first and reaping the benefit later. |

||

So the first feature of our system is the knowledge of how much money to inject into the economy as a function of economic growth. Clearly communities will need to compile statistics on macro-economic performance to do this. In a crypto-based economy, where all transactions are public, this could be made automatic. At defined points in time, the algorithm will emit money and distribute it to the various people and entities deemed, by ratings, worthy to receive it. |

So the first feature of our system is the knowledge of how much money to inject into the economy as a function of economic growth. Clearly communities will need to compile statistics on macro-economic performance to do this. In a crypto-based economy, where all transactions are public, this could be made automatic. At defined points in time, the algorithm will emit money and distribute it to the various people and entities deemed, by ratings, worthy to receive it. |

||

Latest revision as of 15:06, 1 October 2024

Main article: Economic systems

Introduction

We have discussed the idea of paying workers in our ratings system with crypto and perhaps, more generally, paying them based on their ratings. One other possibility is to do away with money altogether and imagine a “gift giving” arrangement based on ratings.

Here, however, we propose a more conventional system where money still exists and its distribution is based on ratings. This simpler step may pave the way to future iterations where money is eliminated. We emphasize that the ratings system itself is neutral on which monetary or economic system is chosen. Communities formed from the ratings system will have complete control over these decisions and can optimize them for their own needs.

Philosophy of money

Money is a proxy for physical goods and labor. The amount of it should be proportional to the amount of physical goods and labor available to buy. If there is suddenly twice as much money in circulation, then everything should cost twice as much (100% inflation). The amount of money in society will thus need to be controlled in some way to keep prices stable for the same economic reasons we want to keep prices stable today. Deflation causes economies to slow down and even contract because no one wants to spend if everything will be cheaper tomorrow. Inflation does the opposite, and causes people to spend unnecessarily in the hope of securing real goods before prices rise. Both cases cause a misallocation of resources. As a result, communities may want price stability and create their own “central banks” to achieve it.

Price stability is normally obtained by controlling the growth in the amount of money to correspond to growth in economic output (ie GDP). If economic output grows by 2% then the amount of money can increase by 2% without inflation. Another way to put this is that if the central bank lends an investor, say $100 million, by “printing” the funds into existence, and that investor then creates $100 million of new goods that people actually buy, then no inflation has been created. If the investor fails to create any new goods then that $100 million simply causes prices to increase. It is like giving consumers a free money gift, totaling $100 million, to spend into the current economy. That increased money will cause inflation.

It is important to understand one central feature of modern economic systems: they create the money first, out of thin air so to speak. Then they hope the money is well spent (or rather, invested). Many people see this is an unfortunate consequence of fiat money but it is really part of the design. If every project we wanted to do had to find existing money to do it with, our economy would be in for a massive slowdown, and no doubt several years of contraction while the new system is adjusted to. Once we settled down we’d have to get used to very slow economic growth thenceforward. Modern economies operate by decreeing the money into existence first and reaping the benefit later.

So the first feature of our system is the knowledge of how much money to inject into the economy as a function of economic growth. Clearly communities will need to compile statistics on macro-economic performance to do this. In a crypto-based economy, where all transactions are public, this could be made automatic. At defined points in time, the algorithm will emit money and distribute it to the various people and entities deemed, by ratings, worthy to receive it.

The remaining issue then is how this money gets distributed, which is the same as asking how society’s goods and services are allocated. Our proposal is to tie this to ratings. Those with higher scores get more money, those with lower scores get less. We could also tie money specifically to work done but then we’d run into the problem of having to price different types of labor independently of the individual contributor (this is discussed more below). It might just be better to have a rating for “contributions to society” and let the system rate everyone accordingly. So here we will explore a ratings-only based system.

A model for income distribution based on ratings

Let’s suppose we have a society with a total income, USD and a population . We can then define a per capital income, :

We now envision a ratings system whose scale is 0-1 where, for simplicity, the average rating is 0.5. We will come to the problem of “ratings inflation” later.

Let’s stipulate that the average rating corresponds to the average income which is simply the per capita income defined above. Thus a person scoring a 0.5 will earn every year. If everyone in society scored a 0.5, everyone would make the same every year, . Furthermore, the addition of everyone’s income would equal the society’s total income, .

Our system will, in general, reward the high scorers and penalize the low scorers. We stipulate a linear relationship between rating and income and we already know a single point on that curve, the income of the mean-scoring individual. To obtain another point we can choose the income of the lowest scorer, as some number generally below the average but above 0:

The idea here is that the community chooses the . Note that an yields a perfect socialistic income distribution where everyone earns the same. By contrast, yields the opposite, a completely meritocratic distribution where no effort is made to help the lower earners. Let’s say in our example here.

Given we now have a way to calculate the slope of the linear relationship:

Slope is normally viewed as rise over run. In this case the rise is the difference between the average income, and the lowest income, while the run is the difference in ratings between the two, 0.5.

The y-intercept is, of course, so the linear relationship becomes:

The is a user input but we can see its purpose a little better by using instead an equality factor, , where :

Thus corresponds to the socialistic income distribution and corresponds to the perfect meritocracy. means equality of income and means there is no equality, ie complete inequality. If we set as we did above,

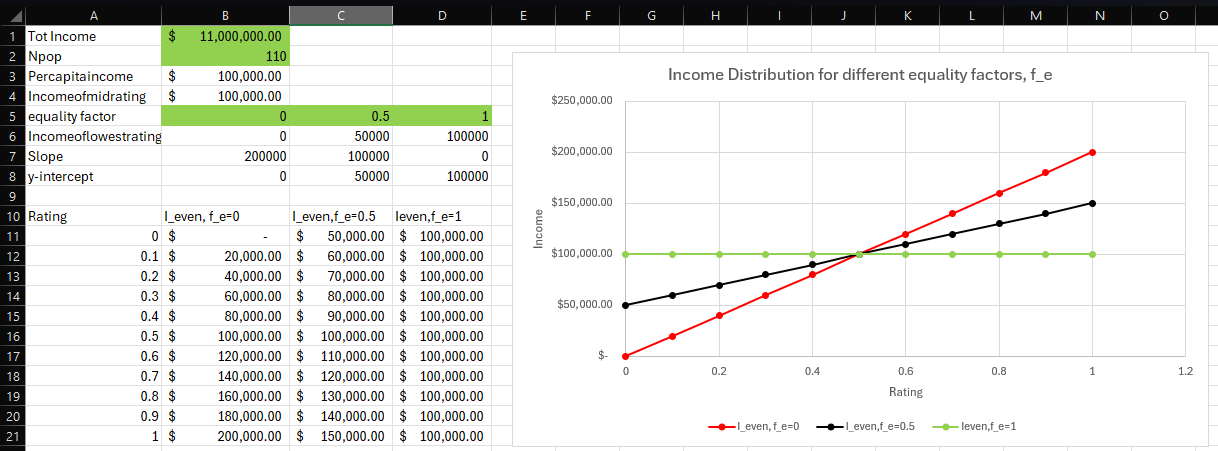

Regardless of whether we input or we can plot the resulting income distribution, as a function of rating, as in the following spreadsheet:

Thus we see that the as the equality factor increases the line becomes flatter, until perfect equality is achieved.

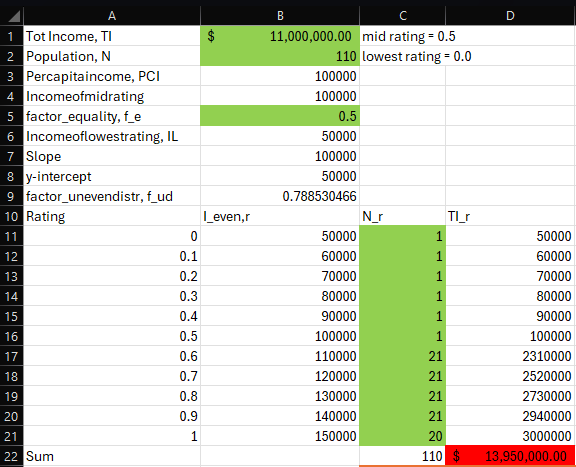

So far we have assumed that the population distribution across the ratings is uniform. So if we have a population of 110 as in the chart above, 10 people occupy each of the 11 ratings categories, assuming discrete slots (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0).

Of course, this isn’t generally the case. In reality we will be inserting an arbitrary number of people in each rating, depending on how our ratings system scored them. If there is a lopsided rating, say everyone near the high end, then the sum of their incomes will exceed the total income for the society, . This is shown in the following spreadsheet where the represents the total income in each rating that would be obtained had we adhered strictly to the even distribution we set out with, . Of course, the total of each (in red) is higher than the total societal income:

Alternatively, if the ratings distribution skews low, then the total of individual incomes will be lower than . Either way, we need a way to adjust the incomes based on uneven distributions.

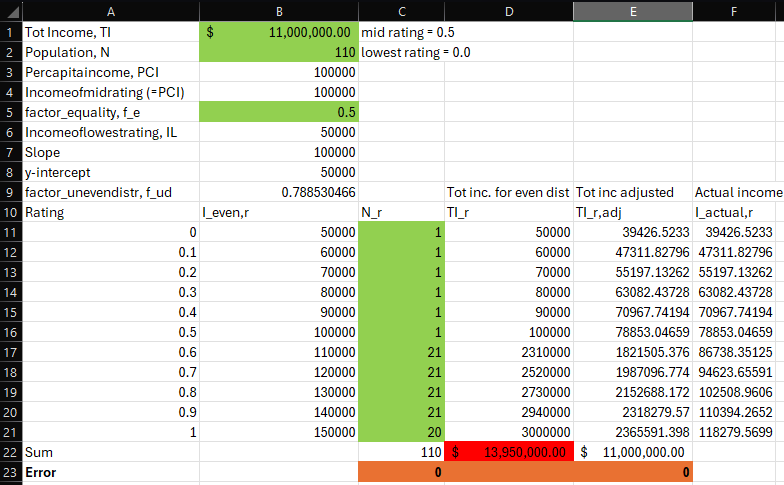

One way to do this is to take and divide it by the total income all the individuals would make if we hewed to the evenly distributed scheme:

Once this factor is known an adjusted total income for each rating, can be found.

Now the actual income of each individual in any ratings category can be found:

The E and F column of the spreadsheet below can be shown which illustrates these calculations:

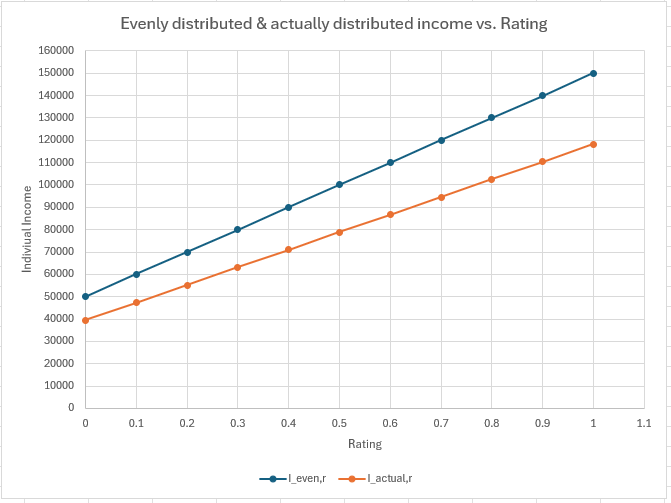

The following graph displays the result of the evenly and actually distributed income. Note that the actual income is less than the even distribution would suggest because the ratings are skewed toward the high side.

The Excel spreadsheet that performs the calculations shown here is attached:ratings_income_distribution.xlsx

Some thoughts on the model

We assumed a linear relationship between ratings and income. This seems reasonable as a first approximation. It implies that a 10% increase in ratings (0.8 to 0.9) should correspond to a 10% increase in income. One could say that such a person is 10% “more valuable”. Obviously this notion can be questioned, particularly in areas related to high skill or talent. A stand-out scientist or inventor (eg Einstein, Edison) might be orders of magnitude more valuable than some closely rated competitors. So although a reasonable argument exists for non-linearity, it is notable that most institutions ignore this and pay their professional staff within much more restrictive bands. In our case, communities will certainly be free to create nonlinear systems. Here, however, we stick to linear relationships both for simplicity and because they seem to mimic most compensation practices.

We also decided on an equality factor, , which brings everyone’s income toward the average. This would be a community-decided idea, of course, but we note that it tends to also correspond to reality. Generally speaking we are willing, in some degree, to spread wealth to the lowest performing members of society. Indeed, we can consider a more sophisticated approach which optimizes income distribution along these lines.

We’ve assumed here that a central bank will exist to grow the total money supply in relation to economic growth. So the money supply is distributed according to ratings, as discussed above, but the amount is based on economic activity since money is simply a substitute for real goods and services.

As ratings change our central bank will likely require a relationship between ratings and economic performance. If ratings go up we would expect economic performance to increase as well. The central bank could use this relationship to predict the money supply required. Although it will also use hard economic statistics, these are laborious to collect and are a few months out of date by the time they are compiled. Ratings will be easy to collect (mostly automatic) and will provide a real-time assessment of the type of economic performance we can expect.

Ratings inflation

Our presumptive central bank would have to assess issues of ratings “inflation”, which simply means undeserved higher ratings. Such ratings would lead to no actual improvement in the economy (no more goods/services). There may be various socio-cultural factors leading to such inflation and we will need strategies to mitigate it. Just like price stability, ratings stability sounds like a desirable feature.

One option for mitigation is to simply use a normal distribution where the mean is 0.5 and the ends of the tails are 0 and 1. Ratings that drift upward for sociocultural reasons alone could then be reset to correspond to a realistic distribution.

This would work as long as there is still a distinct distribution, even if it is upwardly skewed. However, some ratings systems tend to produce a large number of the highest rating (1 in our case) for psychological and cultural reasons that are hard to define. Doing this would, of course, break any economic system based on ratings. If everyone scores a 1, a community has decided that everyone is the same and, from an economic perspective, have chosen a type of socialism. Communities, presumably, would be free to do this despite its obvious negative effects.

Aside from economics, breaking a ratings system by inflating large numbers of people to the highest rating, has pernicious effects. The system would no longer be able to distinguish real from fake information, dishonest from honest people, etc. A ratings system where effectively no one participates is, essentially, not a ratings system at all.

The ratings system itself can combat this in a couple of ways. One is by being able to rate ratings. Ratings that are inflated can be identified as such although it is likely that a culture that inflates the ratings in the first place will discourage calling out overly inflated ratings. Another way is to use anonymous ratings and aggregators (human or algorithmic) that promise to maintain the privacy of their sources. Yet another way might be to focus the ratings on organizations rather than individuals. It’s much easier to rate an organization honestly than a person.

Weighted ratings for economic performance

The analysis above works for a single numerical rating, an aggregate based on a list of ratings for various criteria. Presumably each rating in the list is weighted differently depending on how important each criterion is economically and how it relates to the work that each individual does.

Let’s suppose we have two people-rating criteria: mathematical accuracy and compassion for others. Jack is an accountant so mathematical accuracy is important for him but compassion for others is not. Jill is a nurse so mathematical accuracy doesn’t matter (that much) but compassion does. The economic rating algorithm would need to determine how much to weigh compassion and mathematical accuracy in each case.

Ratings hierarchies like this produce tradeoffs. Jill is a compassionate nurse but if she expresses her compassion with every patient in the hospital she’s unlikely to get anything done. She must also possess some measure of effectiveness to go along with an otherwise admirable instinct. Likewise Jack, if he’s too obsessive about accuracy, will likely spend too much time on every calculation and stop being effective. The algorithm will have to decide the optimal mix of characteristics and then calculate how far away each one is.

Raising investment capital

As we’ve stated, traditional monetary systems create the money first and then hope the economic output follows. Our system can choose to do this as well, although it wouldn’t be required. Once ratings are known, our algorithms will be able to distribute income and, if the ratings improve, will be able to grow the money supply to account for the expected economic performance improvement.

But what if someone has an idea and they need investment capital? Our usual method in today’s society is, roughly speaking, to simply create the money, give it to them, and hope for the best. On balance this works out. The Fed produces money “out of thin air” and the subsequent investments usually work out, that is, they result in substantive growth over inflation. If we look at our economic output today compared to say, 1920, we have become greatly wealthier in real terms. There was also inflation, to be sure, but it was not equal to the growth. Almost anyone living in a western industrialized country would rather be alive today than in 1920.

So our system would also give investors the money and hope for the best. Communities can use the ratings system to decide how much a project should be funded and then tell the crypto algorithm to simply create it. The money will then be tracked to buy the necessary goods (or services) needed, thus reducing the incidence of fraud. Naturally, the ratings system decides how worthy such projects are and, once they payout, we will be able to transparently evaluate their economic return.

The problem with pricing labor

Currently, since labor categories are priced by the market it is difficult to distinguish individual contributions. Engineers make more than schoolteachers but is a bad engineer really worth more than a great schoolteacher? Capitalistic pricing is based on nothing more than what someone is willing to pay. So if a company is ok with keeping a bad engineer on staff and paying them at the rate (more or less) that engineers are usually paid, there’s not much we can do. Similarly a great schoolteacher will be paid within some constrained band where all schoolteachers are paid. Again, this is very hard to change.

A ratings-based payment system can more accurately understand the difference between real contributions, no matter what field they are in. By rating people and their characteristics we can relate their likely contribution to society with economic gain more effectively. Of course, someone might decide in such a system to fall asleep and stop doing work. After all, their rating should keep them afloat, right? No, because a rating will also exist for laziness, or how hard-working someone is. An attempt at fraud would be detected by the system itself and would necessarily weigh heavily in any aggregate rating.

What's wrong with the Fed?

We’ve discussed some ideas here to replace our current monetary system with one based on ratings. But we’ve also mentioned the creation of community-based central banks to do much the same task that our current central banks do, ie control inflation and ensure economic growth. This task, in and of itself, does not seem objectionable and the US Fed, as one example of a central bank, has done a reasonably decent job of this. There has never been hyperinflation on its watch and, if anything, monetary policy has historically been too tight.

The real problem with the Fed is that it sets monetary policy for the entire country. This is such a large entity that it is hard to see how a single agency can optimally do this. We don’t expect a government agency to reasonably decide the number of cars produced in the US every year, or to determine their price. The Fed does both with regard to money, arguably the most important “product” in the entire economy.

The Fed is also shielded politically since, beyond its basic mandate (to minimize inflation and unemployment), it acts independently of Congress and the President. This is regarded as a necessity since otherwise venal politicians, with no understanding of economics, would influence it.

But this is not an optimal arrangement. It would seem that, first, our ability to create money should exist closer to where actual value is created. The people doing the creating and rating the creating should have a better handle of how much value is produced and what the correct monetary policy should be. In our case communities will get to decide on monetary policy. Second, we’d have political accountability in the form of the ratings system itself for the monetary creation policy. If the policy is considered too risky or too conservative, this can be brought out in the ratings system.