More actions

Main article: Economic Systems

INTRODUCTION

We have discussed a monetary system based on crypto that communities could use to pay people based on ratings and purchase goods in the economy. We've also discussed a system of “gift giving” using ratings which would involve no money at all. Here we propose a system that is somewhere in the middle but that takes us one more step from a moneyed system to a moneyless system.

A MONEYLESS COMMUNAL ECONOMIC SYSTEM

Let’s imagine a community that is small enough that everyone knows each other. This could be a family, traditional village, social club, etc. The ratings system is thus intuitive and just held in everyone’s mind. People work within the community to do something, either produce goods or provide services. They also derive something, either in the form of goods, services, or intangible social benefits. No one accepts money for these activities.

It is not exactly clear how such economies work since they depend on informal rules of allocation and ratings. It would seem they are governed by a spirit of mutual welfare with some favoritism reserved for those higher in reputation. They have proven to be remarkably durable and effective, at least on a small scale. We stress that they are not fundamentally barter economies even though barter might play a role in them. In the economy we develop here, we will not consider barter since barter is just a precursor to money.

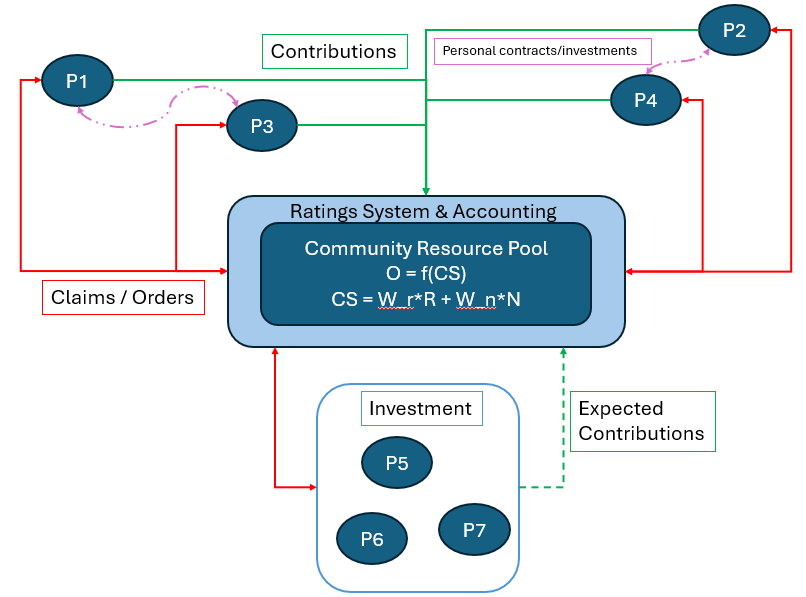

In many ways the system we are considering has its roots in communal economic systems. Here we will describe how a community-based moneyless economy could work in the context of a formalized rating system. All goods and services are provided to a community pool for subsequent distribution. Once in the pool, consumers will have access to them through an online shopping format (eg Amazon). Ordering something would involve submitting a claim for the product or service in question. The system would collect orders over some time horizon, say a week, and then begin the distribution process. In the case where the supply in the pool of a particular product exceeds the number of orders, everyone’s order is fulfilled. This is a post-scarcity situation. An peer-to-peer alternative to this idea can also be considered.

In the case where orders exceed supply, goods would be allocated according to the claim-strength of each individual. The claim-strength is a weighted combination of rating and need. The need is a statement made by the individual of why they need the item and is, itself, ratable by the community. If someone without a single chair in their home claims to need one, their need will be high and their need-rating should reflect that. If someone who already owns 40 chairs claims to need another one, their need rating will be low. If this person lies and says they don’t have any chairs, they can be downrated for both dishonesty and need. The weak claim then affects their rating long term because they have shown themselves to be taking advantage of the system. Assuming the need is equal, the chair will go to the person with the highest rating.

The basic formula for claim strength, is:

where

is the Rating of the person making the claim

is the Need of the person making the claim

is the weight for the Rating

is the weight for the Need

The ratings system will already supply . will also be supplied by the ratings system based on a written statement of need from the claimant. To simplify this, we may allow the claimant to submit their own plus a written statement and allow the community to respond to that claim. This would be in contrast to the default procedure where the community provides directly based on the statement and their knowledge of the individual.

Another option to reduce “paperwork” is to simply use an honor system for claim need and perform audits later to assess the integrity of the claims that appear questionable. This is similar to how IRS audits work except our audit system would be rated for bias, effectiveness, etc. Such a system would presumably be rigorously governed by community standards.

Claims dishonesty could probably be pre-empted largely through an accounting system which would know what everyone has (or has received). Much of this could presumably be automatic. Those who wish their claims and orders to be private may do so but it would cost them in ratings for transparency and their need may be doubted. Obviously a very private but very honest person will be so rated and their need claim would be believed anyway. Nevertheless, those who submit to being tracked by the accounting system will generally receive better marks for claims honesty.

Judging from the orders someone makes, the accounting system will be able to ascertain, to some extent, someone’s need for a particular product. If someone with a low default need makes a claim, then they would have to justify it to increase their claim strength. Maybe they are having kids and need more chairs or maybe they are starting a factory and need chairs for workers to sit in.

The accounting system will also need to match demand with goods produced, which should be fairly simple given that claims for goods will indicate exactly what is required. Labor services will also be placed in the pool for distribution. Estimates for production will then be made based on claims from the past, the known availability of labor, capital production equipment, etc, all of which will be tracked by the accounting system.

What motivates people to work in such a system, to invent, to think outside the box, to advance unconventional ideas? We presume that in capitalism, it is the reward that comes from monetizing a good idea. But many people have unconventional ideas, invent things, etc. with no monetary reward. The vast majority of inventors work for companies and most scientific discovery is done by people who work for academia, nonprofit labs, etc. Although there may be some financial incentive in their creativity, it is a modest sum compared to the potential wealth that is had by the commercial monetizers. These tend to be marketing and business people who are good at sales. It’s not that sales is worthless but it does not appear to have any inherent merit over any other worthwhile human activity, and certainly not orders of magnitude greater.

POST-SCARCITY SITUATIONS

Wealthy societies are largely post-scarcity societies. That is, they can easily produce enough essential goods and services for everyone. This is especially true for small-ticket, everyday items such as food and household goods. It is also true for ongoing services such as education, medical care, etc. Post-scarcity goods and services will be labeled as such and will not require written claims, or evaluations of claim-strength, and all such orders will simply be filled. However, the ratings system can still watch this activity for evidence of hoarding, or other malfeasance, and step in to call it out.

A prosperous enough society will conceivably reach a post-scarcity situation in almost all its goods and services. The US per capita GDP is around $80,000/yr and is, save for income distribution issues, already a post-scarcity society. It may not feel that way today both because of inequality and artificial scarcity imposed by powerful and self-interested parties. Medical care comes to mind. The presence of luxury goods (those on the flat part of Pareto curve), a direct result of wealth inequality, also distorts our thinking about what is really scarce.

The ratings system will ensure that post-scarcity production levels are reached because it will rate more highly those producers who meet society’s needs. As in our society, there will also be some demand for luxury goods that may actually be scarce. This should be considerably lower if we’ve solved the wealth inequality problem, but it will likely still exist. Since no one will actually “need” these goods, their distribution could be governed by the ratings system alone, without the need portion of the claim strength. We will be allowing, thus, a certain amount of competition for luxury items in the recognition that a segment of society will always be motivated by this.

If the acquisition of basic items is guaranteed and the acquisition of luxury items is limited, what then motivates people to produce, create, and do their best in this system? We discussed motivation above and the basic answer is that, aside from intrinsic reasons, most people are motivated for social reasons. For reputational reasons, to be specific. Reputation and social standing motivates students to excel in school, scientists to publish, and soldiers to risk their lives in battle (for which no material recompense is possible).

A natural question arises now which is if society is able to produce in excess of what it really needs, what do we do with this excess capacity? Well, one answer is that we might just allow people to work less. Cultural norms will probably be established (enforced by ratings) such that allowing people more time off is a realistic possibility. Others, however, may want to produce, to work for society’s benefit with their extra time. Some of this excess production will turn into, if not more, then higher quality goods and services. Even in essential items, there is always room for innovation and improvement. There are also side effects of consumption, such as waste and pollution that need to be solved. In essence then, overproduction will be transformed into an investment in society and will be rated accordingly.

We can also reasonably ask what post-scarcity means in a society where we invent new things that people come to think of as necessary. Computers were not a necessity 40 years ago but they are today. Societal norms, governed by a ratings system, is probably the most accurate arbiter of how necessity is defined.

INVESTMENT IN A MONEYLESS SYSTEM

In a moneyless society investments are just claims. If a new project is proposed, it puts forth a claim for society’s wealth, a specific one, and tells what the expected benefits are. This forms the claim strength of the project and it competes with people and other projects for resources. The investment claims will be rated by the community and will affect the people making them.

Clearly people and proposals will compete with each other. Communities might have rules for allocation that prioritizes people first. In a post-scarcity society a community might require that basic needs are addressed to some minimal level before investment needs. Post-scarcity societies shouldn’t have any trouble doing this. Still, communities will want to balance this since allocating all resources to people and none to investment will have its own pernicious consequences.

The claims system will have an inventory of all the goods and services available in society. Claims will then have to match these goods. We’ve imagined an Amazon-like shopping experience where we claim the exact items available. This would be easy enough for individuals to do but for investment proposals we often don’t know in advance the exact model numbers of everything the effort will need. In this case, the proposal can make an estimate which will be matched to actual goods/services through an estimating algorithm. It would seem that proposals of this kind might actually be better than current ones that simply ask for money. The proposers will need to think through their needs more rigorously and, once the project is “funded”, will need to generally spend their allocation in the prescribed way, which would be easy to track. Some allowance could be made for swapping items or requesting new resources due to estimating errors.

Most of the investment money in developed nations is done through private loans. Government investment projects are, similarly, usually funded with credit since tax receipts are generally assigned to ongoing money transfer programs. The US government typically runs a substantial budget deficit to cover these investments (among other expenses). Keep in mind that a loan is a new claim on resources, one that is, in a sense, unexpected. A small but important level of investment is also made by venture capitalists who already have the required funding on hand and are simply transferring it to the entrepreneur. Venture capital is the only sector not making a new, or unexpected claim, since the resources being used have already been created.

Loans lay claim to real goods in the economy, making those goods less available to the public. The public, indeed, is not really aware that this is taking place but they should be. In essence, society’s wealth is being appropriated for the purpose of some future good. When the government does this there is some small measure of accountability. The public is vaguely aware of government programs, the deficit, that they are being taxed, etc. Presumably they voted for these financial arrangements. But no such democratic process, however flawed, takes place with private loans. Banks have the power to create money (aka claims on resources) arbitrarily and enable their borrowers to compete for goods with consumers. And the central bank, the ultimate arbiter of this power, is not politically accountable except in the most abstract sense.

In our moneyless society, communities will decide how much investment to make which, generally speaking, will involve a reduction in the amount of wealth they can have as consumers. Investments will be rated like all community programs and citizens will decide what they are willing to sacrifice.

Venture capital investment could also exist but would likely be substantially reduced in a society with a more equal distribution of income. Today, venture capitalists are possible as a result of unequal income distributions which allows a small class of people to acquire great wealth. To their credit, they sometimes use this wealth to invest in worthwhile projects, particularly in high tech areas which are inherently risky and do not have the physical collateral to back a traditional loan (eg software idea, salaries for programmers).

This is an important point to pause on. We are proposing a society in which investment is performed by a consensual community, ie the government in today’s parlance. Those of a leftist persuasion may find nothing of concern here, but it is a change so fundamental that it merits at least some consideration. And, needless to say, not everyone is of a leftist persuasion.

The main case for private investment is that it localizes the process to the few individuals who know the most about the new business idea: the person who has the idea and the investor. The idea person only has to convince the investor to invest. In the public system, the idea person has to convince the public, or the community, to invest. The government has agencies that provide funding to small businesses, but these normally have to meet specific criteria, namely that they are doing something scientifically “new”. Incremental improvements, the kind that generate most of our new businesses, don’t normally count.

Our system does not preclude private investment but, without money, how does this take place? There may be cases where individuals or groups save enough excess wealth to invest. But how would “savings” take place? This is where it gets hard to divorce ourselves from money entirely.

People could, for instance, lay claim to resources and decide that they really don’t need them, thus sending them back to the pool or not taking delivery of them in the first place. The community would account for these “savings” by simply writing a note saying that the claimant is owed the goods at a future time. This IOU is then a debt which the claimant can use later to claim the goods and services. The IOU could also presumably be given to another individual who could claim those same goods. This presumed IOU is already a form of money. The new holder of the IOU might then “owe” the original holder interest. We could conceivably calculate the interest in physical goods and write a note to that effect, thus creating more “money”. Or we could assign a number to the interest and then price goods in terms of that number.

It seems here that we’ve created a very quick slippery slope to money, all due to the decision to have private investment. In a fundamental sense, money creation is a private matter, arising primarily from the right to engage in contract. One example is Ithaca Hours, a private money system used by local businesses and consumers in Ithaca, NY. Several such money systems exist and show that money is a concept that arises naturally among people, even ones used to using the US dollar. Historically, our central bank’s monopoly on money creation evolved from these private beginnings. It would appear that only economic complexity and government power transformed it into the monopolistic standard it is today.

We can note here that perhaps our community-run system of investment will prove as effective as our current private system. The more equal distribution of wealth, and certainty of being “paid”, will permit people to more objectively judge the merits of publicly fundable ideas. They wouldn’t depend so much on the private instinct to make money but rather on a public instinct to do the right thing by taking prudent risks. It is also of note that venture capital wouldn’t have to fund salaries at all in our system, making the funding of ideas cheaper and more palatable to the community at large. It would also make “venture capital” more possible for private individuals, should they choose to invest their own resources.

As for the slippery slope to money, we could separate the consumer and business sides of the economy. This would allow us to have money for only business investment while consumers would exist in the moneyless system described above. We might introduce to this a consumer form of credit for big ticket items like houses whose acquisition is normally justified in terms of the future earnings of the buyer.

ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES, DEFLATION, etc.

The economic system as conceived here is likely to produce a more egalitarian distribution of wealth. Indeed it is more like how a family works in the sense that everyone contributes and consumes from a common pool. Those who are deserving naturally get more but everyone is provided with a fairly standard floor. A moneyless system also allows us to more easily do away with unproductive institutions based on money, such as intellectual property.

It is conventionally understood that we should avoid deflation because it drastically slows down the economy and reduces the pool of investment capital. On the other hand, this wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing because it would reduce frivolous consumer spending, save natural resources, etc. With a claims-based distribution system we could have the best of both worlds because it introduces some friction into the consumption process but does not, in and of itself, cut us off from allowing organizations to claim resources for investment purposes.

UNEQUAL WEALTH DISTRIBUTION

Jeff Immelt, the former CEO of GE, was paid $200 million to leave the company after being widely blamed for presiding over its failure. This year, under new leadership, GE is completing the result of that failure, its breakup into 3 distinct companies.

The CEO of Procter and Gamble, a company that makes laundry detergent, toothpaste, paper towels, etc. was paid $22 million in 2022. The company spent $4.3 billion advertising products in 2015 that are already very well known. Their CEO to median worker pay ratio was 309, compared to 141 for S&P 500 and Russell 1000 companies.

What did either of these individuals actually contribute to society? Apart from the spectacular downfall of GE, if you read their bios you will discover that they led fairly average lives. They went to college and then got jobs. Both of these CEOs got MBA’s. They rose through the ranks of their respective companies but they were never innovators or particularly good strategists. They just went to work every day. Their main function, apparently, was public relations.

No conscious system of economic allocation would do this. CEO compensation is the result of unconscious market and social forces that produce wildly suboptimal results. One defense of the system is that it is the result of market competition for the best leadership. Some argue that these CEO’s are worth what they are making because the stock price went up under their watch or the company developed some successful new product. This can certainly happen but it is not the norm and, in any case, fails to justify the sheer magnitude of the compensation packages.

Most people imagine wealth redistribution to involve taking money from the rich and giving it to the poor. This has proven politically difficult, to say the least. Our ratings-based economy can avoid that by choosing to not allow that much wealth accumulation in the first place. Rewards for good character and good work will certainly be available. But grotesque wealth, the kind we see regularly in the US, will be preventable through a community of raters.