More actions

Main article: Trust

Trust can be looked upon as the probability of an interaction with someone having an expected favorable outcome. This might mean they tell the truth when asked a question. Or it might mean they don’t cheat you in a financial transaction. The outcome must be expected because normally we don’t count on random outcomes, even if they are favorable. And the outcome must be favorable because that is, presumably, the reason for the interaction in the first place. More generally, trust in a person can be viewed as the overall probability, taken over many interactions, that future outcomes will be favorable.

Trust is based on prior interactions and its accuracy depends heavily on sample size. A single favorable interaction with someone does not confer the same level of trust as 100 such interactions. Our trust level should converge to some value after many repeated interactions with someone.

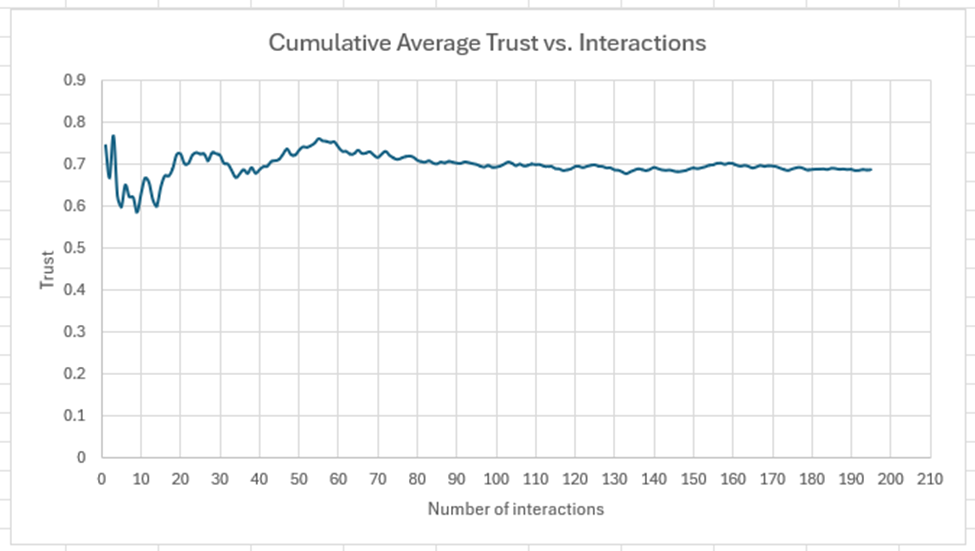

The following graph illustrates this for a case where someone’s average level of trust is 0.7. Here, each interaction is rated for favorability, between 0 and 1, and the cumulative average favorability is set to 0.7 (our trust level). Indeed, it takes roughly 80 interactions to reach a settled-out view of their trust, although we’d have a fairly good idea after about 30 interactions.

Trust is, of course, more complex than a simple random analysis like this would suggest. Many people are more consistent in their interactions such that, in this case, each interaction would deviate more tightly around the 0.7 than this graph suggests. In that case, it would require fewer interactions to establish a reliable average trust.

But trust has many more complex aspects to it. We often have to calculate trust on the fly with people we don’t know very well. We resort to heuristics and trust by association. We hire people if they have the background we want and “seem ok” in a single interview. We trust the bank teller to honestly handle our money even if we’ve never met her before. And, needless to say, even the most rigorous calculation is subject to statistical error. Over a period of time, we continue to adjust our number up or down depending on the objective outcome of various interactions.

It is important to understand how trust is derived and to separate out the various components that make it up. This enables us to precisely differentiate between our problems (inability to predict) and someone else’s problem (choosing to do wrong). When we rate other people, we want to rate them fairly on the basis of their inherent properties (eg morality) and not on our own inability to predict them because we don’t know them that well. How often have you answered a question about someone by saying “well, they seem nice but maybe they’re an axe murderer at night”? A good ratings system should cleanly distinguish between the methodologies being used.

It should also account for another human characteristic, the tendency to give people the benefit of the doubt. If we don’t know someone, we generally assign them a baseline level of trust. We do not automatically assume that people are untrustworthy because we don’t know them. This too is a recognition that our knowledge of someone is frequently lacking, but we know that it is probably ok to deal with them in some limited way. Our ratings system should probe for the reasons for trust levels and categorize them appropriately. Fortunately, by integrating over large numbers of people (ie interactions) the ratings system enables this possibility.

Context and culture obviously matter a lot in trust. If a stranger on the street asks you for a large loan that they will pay you interest for, you would probably be unwilling to trust that person. But we are willing to walk into a bank and deposit our money with equally complete strangers. The fact of the bank is important. But so is the fact that it is normal to walk into a bank and hand them money for deposit. It is not normal to do so with a stranger.

Note how this asymmetry of trust greatly favors the centralized institution. This is rational up to a point. The bank, for instance, is not likely to “run away” with your money but the individual might. The bank can, furthermore, spread its risk so even if it does something stupid with your money it will be able to cover your deposit using someone else’s. And the bank is presumably already trusted because it already has many customers. It wouldn’t exist otherwise. But the monopoly of trust enjoyed by the bank seems to go too far. There is no “banking industry” at a small-scale individual level, offering higher interest rates (let’s say) for the objectively higher risk its customers would be taking.

The same is true for many institutions that, to put in pointedly, hoard trust: insurance companies, hospitals, companies that sell consumer products. Size matters in large part because trust rises in proportion to it. The law frequently magnifies this trend with naturally favorable treatment of organizations that have the heft to comply with its regulatory requirements (and have political influence).

This has two negative effects. The first is that we have learned to rely on institutions rather than each other, thus weakening community bonds. The second is that the institutions themselves gain too much power. It’s a difficult problem to get out of once a culture has accepted it.

A functioning ratings system is obviously the antidote to all this. If the bank has a built-in ratings system, because of its customers, the individual would have the same with our ratings system. Someone with high financial trust could offer, for instance, personalized insurance services at lower cost because they know you better. Or banking services at higher interest rates. Meanwhile the ratings system will also be accurately gauging the trust assigned to institutions, to make sure it is deserved and not just an assumed value based on size, advertising, or some other irrelevant factor. Again, this brings to mind the importance of ensuring that we know exactly why people trust as they do.