More actions

Main article: Ratings system

Voting methods, or voting systems, refer to systematic techniques by which communities make democratic decisions. A vote is essentially an expression of preference for a certain option over another. It is a type of rating whose purpose is to decide on a candidate for public office or to make a public policy choice. A related concept is polling which will be an important application of the ratings system.

Traditional voting

Let's first take a look at the standard way to elect representatives in the US (and other English speaking countries), "first past the post" or plurality voting. This system designates the winner as the candidate receiving the most votes. Usually there is only one winner (aka "winner take all") for an entire district.

This system has the virtue of simplicity but comes with serious drawbacks. One is the basic problem, which is that winners can easily emerge who have not received majority support. This problem is usually paired with the fact that there is rarely a runoff election to force a majority. As a consequence, it is easy to have a 3rd party spoiler in a system like this. Ralph Nader, for example, cost Al Gore the 2000 presidential election because he won around 100,000 votes in Florida while the vote difference between Bush and Gore was only 537. It is possible that Ross Perot did the same thing in 1992, costing George HW Bush his re-election in favor of Bill Clinton. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. could do the same in what is expected to be a close election in 2024.

This system has the interesting effect of producing two dominant parties. Third parties, if they're even on the ballot, tend to run way behind. Why is this? For 3 parties you would need to consistently have a situation where all three were fairly close, around 33% of the vote, and any one of these could thereby go slightly above it and win. This could theoretically be true but there are many more ways for it not to be true on simple probabilistic grounds. Furthermore most voters, knowing the rules of the game, are not inclined to throw their vote away on a party perceived to be weak.

Perhaps a more fundamental reason is that the two major parties represent the two major ideological differences we have, right and left. There doesn't appear to be a third ideological option although many have argued for a third party that, for instance, is conservative on economic issues but liberal on social issues. If we could establish such a party and it could consistently compete at around the 33% mark we could have some type of rotating three party system.

So why does this never happen? Probably because the fiscal conservative/social liberal ideology doesn't really exist in practical electoral terms. Those who feel this way end up voting for one of the two parties because they feel their conservative economic position is more important than their liberal social position, or vice versa. Indeed in many cases the traditional two parties are savvy enough to throw a bone to the hesitant voter and convince them. Pre Dobbs, economic conservatives/social liberals have tended to vote Republican because the party convinced them that their abortion restrictions would be modest and hinted that they wouldn't be pursuing them vigorously anyway. Even today we are seeing a majority of Republicans uniting behind Trump despite their misgivings about his behavior. Indeed, no anti-Trump conservative party has ever emerged.

How can a system like ours counter the two-party problem? Clearly a bipolar political alignment is completely at odds with what we are trying to achieve. If anything we want a multi-dimensional approach to politics and ideas that transcend our banal left-right scale. Our system cannot, obviously, take over the government or its election system. But it can exist as an alternate election platform and an alternative form of government. Elections can be held, policies debated, and the effects of policies can be analyzed. For elections, the system can consistently show the result of alternate approaches to voting, like having runoff elections, proportional representation, cardinal systems, etc. Our system could even have political parties through its community involvement features. With enough participation our software will reach a critical point where, de facto, it will begin displacing existing institutions.

Ranked choice and other voting systems

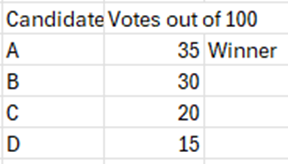

Ranked choice voting (RCV) has become a popular alternative to first past the post (FPTP) voting in the US. FPTP is the plurality winner system where the candidate who receives the most votes wins. The obvious problem with it is that a candidate decisively in the minority can win:

When we add to this other complicating factors, such as the electoral college, itself based on state results which are largely FPTP, we can obtain winners who lose even by plurality if we count all votes nationally.

Here we will consider two alternatives to FPTP, ranked choice voting (RCV) and Condorcet voting (CV). These are considered the “best” voting systems for single winner cases according to fairvote.org.

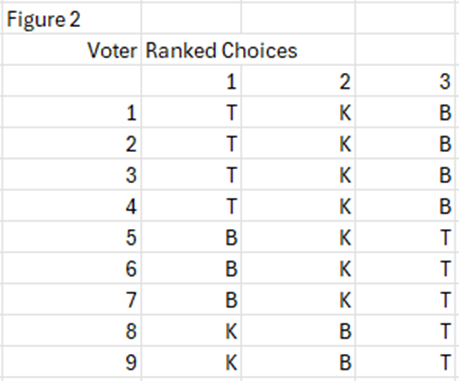

Let’s look at a hypothetical matchup with 9 voters between three candidates, B, T, and K.

In FPTP, T wins because he receives 4/9 votes and this is a plurality, the most votes of any other candidate.

In RCV, B wins for the following reason: The method eliminates the lowest scoring 1st choice vote getter (K) and assigns their 2nd choice votes (B) to the remaining candidates (see Voter 8 and 9). Thus B receives 2 more votes and wins the election by a 5-4 majority. Note that in RCV if a clear majority emerges as a first-choice vote, then that is the winner and we don’t have to consider further “rounds”.

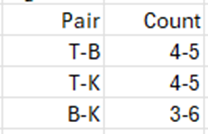

In CV, K wins for the following reasons. The method first lists all potential pairwise matchups and counts the votes for each:

For the sake of complete clarity, let’s look at the T-B matchup to understand the count. If we look at voters 1-4 they all preferred T to B so T wins 4 votes. If we look at voters 5-7 they all preferred B to T since they preferred B to all other candidates. But voters 8-9 also preferred B to T even though B was their second choice. This gives B a total of 5 votes in the T-B matchup.

The table shows the counts for all the potential pairs. Clearly, K beats both B and T in a pairwise matchup.

It should be noted that RCV, despite its failure here, is considered “Condorcet friendly”, in the sense that in most practical elections it picks the Condorcet winner.

So here we have three different systems and, without trying very hard, we obtained three different results. Obviously our voting system has a great deal to do with how our democracy works.

Which voting system is best? FPTP, the one we use most commonly here in the US, probably has only one virtue: simplicity. In an age of computers, however, this doesn’t seem like a serious advantage. RCV is also rated higher than CV for simplicity, but this is only because its counting algorithm is simpler, a weak advantage for the same reason. Sometimes simplicity is concerned with how well voters understand the counting technique. There is no doubt that FPTP fares better here than RCV or CV. But between RCV and CV it seems hard to tell. CV requires potentially more algorithmic “thinking” to come up with the pairs but is an easier concept to grasp intuitively (pretend there’s two candidates and count votes).

So if simplicity is not a valid concern, what is? The website mentioned previously discusses a number of criteria, such as resistance to spoilers and strategic voting. None of these seem to get at the central problem of what is actually the most democratic method in the sense of what best represents the will of the people. Needless to say, it doesn’t give us any insight into what is actually best for society either.

Our example above clearly shows RCV and CV to be more democratic than FPTP. But RCV, after the first choice round is over, takes the second choice selections of the losing voters and makes them first-choice votes. In other words, these voters’ second choices act like first choices. After two rounds it would be those voters’ third choices acting like first choices, and so on. This somehow doesn’t seem right. It seems like a ranked list, as an expression of voter preference, should rank lower candidates lower. So the second choice might have, say, 50%, of the weight of a first choice candidate (100%). This is difficult to do in practice since the US maintains a policy of “one person, one vote” so we can see how a weighted system would violate that. Our new society, however, would not have any such restrictions.

On the other hand CV acts as if voters would behave the same way toward a pairwise matchup as they do in their ranked preferences. There is good reason to believe that they wouldn’t because in a real pairwise matchup they will have more information about the 2 candidates than they did for the ranking, which has many candidates. This is especially true for candidates they ranked lower than first or second.

But this weakness in CV is also a weakness in RCV. In both cases the ballots are the same and the voter is asked to rank their choices. Lower ranked choices in RCV will also suffer from the lesser information the voter will have about them. The problem in RCV is that these lower ranked candidates then have an outsized effect, as if they were first choices, in subsequent counting rounds. One could argue that CV also has this problem since pairwise matchups are counted, by definition, as first-choice votes. But CV does not eliminate, a-priori, the lowest first-ranked vote getter and RCV does. Instead, it looks at all combinations and counts all preferences.

This is really the difference between the methods. RCV eliminates lower preferences to favor the two top vote getters and CV does not. This makes CV the more “complete” method even though it may be a little more complex to perform the counting for, a weakness ameliorated quite easily through software. But this is not the only advantage of CV.

In our hypothetical matchup between T, B, and K we noted that CV ended up electing K, the least favorite first-choice candidate. In the US, K would be the third party candidate who almost never wins since FPTP systems tend to favor two-party rule. But K in this case represents the best compromise candidate, the one most in the middle. In the sense of reconciling differences, K would appear to achieve that. If B and T are viewed as polarizing figures, then electing either of them is certain to perpetuate political rancor. But K might be acceptable enough to all parties to minimize discomfort.

We might note that K in real life (Kennedy) may not seem like such a harmonious figure to many people. He takes a quirky mix of positions, at least by conventional standards, on both the right and left. His strength, though, is that he takes 2nd place for B voters who hate T and T voters who hate B. In this sense, he is indeed a center candidate and, as a result, certainly represents a compromise of sorts. And regardless of K’s actual platform, if we had a CV voting system, we would most probably find ourselves with many more reasonable contenders for the job. Third party candidates would no longer have to see themselves as spoilers for preferred major party candidates, which is exactly what they are in FPTP systems. In fact, given its predisposition toward the middle, CV would probably produce major party candidates who are themselves more reasonable. It is clear that FPTP gives extremists an edge simply because they can win with a minority of the vote.

An interesting website, the Smart Voting Simulator, allows users to play games with different voting methods. It advocates CV methods precisely because of their “find the middle” tendency.

One way to avoid the problem of lower-ranked candidates assuming more importance than warranted in RCV (and CV) is to have runoff elections. The practical manifestation of this is the two-round runoff where the two highest vote-getters in the first election go to a second round and other candidates are eliminated. The exhaustive runoff is the same idea but with more rounds: We eliminate the lowest vote-getter and proceed to have another election with the remainder until only two candidates are left. This is exactly analogous to RCV but with actual elections instead of a single ranked vote. The runoff election is usually held a few weeks after the previous election, which gives voters time to reassess the candidates and prevent the problem of “low information” votes discussed above. Obviously, there is a practical limit to how many elections can be held which is why the two-round runoff is usually favored.

Cardinal Voting Systems

The methods referred to above are examples of ordinal voting systems. As the name implies, ordinal implies an order of preference. Selecting an order, even if it's just voting for a single candidate, is usually what we do in conventional elections. Ordinal voting systems are generally subject to Arrow's theorem which can cause cyclic preferences when more than two choices are considered.

Cardinal voting systems are a little different. Here, the voter assigns a weight to each choice. Suppose Alice has 10 preference points (the weight) to assign to candidate A, B, and C. She assigns 6 points to A, 3 points to B, and 1 point to C. In the same manner, every voter in the electorate assigns their own preferences to each of the candidates. The points are added up and the candidate with the most points wins. Cardinal systems thus express not only preference ranking but also the degree to which the candidate is preferred.

Cardinal voting systems are sometimes called scored voting, approval voting or, for a specific example, STAR. STAR stands for Score Then Automatic Runoff. In this system the candidates are given scores of 0-5 by voters and the two candidates with the highest scores are selected. Each of these candidates is then tallied in the usual single-vote manner based on how each voter felt about them relative to their competitor. The runoff phase is therefore counted the same as a regular election.

The main problem with these systems is that there is nothing to prevent the voter from scoring their preferred candidate a 5 and everyone else a 0. This, in fact, is the logical thing to do because it maximizes the preferred candidate’s chances. The idea is that the voter wouldn’t want to provide any advantage to their less preferred candidate because, when the vote is counted, it might give them enough points to win. But if every voter does this, the system reduces to a regular ordinal voting scheme. The idea behind the runoff system in STAR is to prevent this type of strategy. That is, honestly rating the less preferred candidate doesn’t provide an advantage to them that will be used later, because that voter’s preference will be counted in the runoff anyway. But this only works for sure in a two-way race. In a multi-candidate race, a voter’s nonzero score for a less-preferred candidate might knock out their first choice candidate. This is the main reason why fairvote.org prefers RCV over STAR.

Here is a more in-depth look at cardinal voting systems.

Multi-winner systems

The systems discussed so far are only for single-winner elections. Voting systems become simpler (and fairer) if we have multiple winners because these, by default, ensure that more voters are represented. A multiple winner scenario would have legislative districts, say, represented by a group and the group would be apportioned according to the vote in the district.

There are various ways of doing this. In RCV we would do the usual elimination rounds until the number of remaining candidates equals the number of seats. Then we would calculate the percentage of remaining first choice votes for each candidate and apportion seats accordingly. In CV we could do something similar, creating all possible paired combinations, selecting the winner for the 1st seat, then from the remaining combinations selecting the winner for the 2nd seat, etc. until all the seats are filled. In many countries that use multiple member districts, the vote is done by party and the party sends representatives according to the proportion of the vote. If a district has 10 representatives and 40% voted for party D, 50% for party R, and 10% for the G party, then the district would send 4 D representatives, 5 R representatives, and 1 G representative. Regardless of how it’s done, in multi-member districts many more of the district’s voters are represented. Obviously a lower bound must be established (in this case 10%) so very small parties would not be represented at all. US federal elections, btw, are single-district by law.

Vote cancellation and bias

In the Myth of the Rational Voter, Bryan Caplan argues that most voters do so in a completely uninformed way. We’ve all heard about the level of ignorance: fewer than 25% of voters know who their senators are, only half know that their state has two of them, about a third of voters cannot name even a single branch of government, etc.

However, a situation in which 90% of voters (let’s say) are ignorant effectively cancels out leaving the 10% of the informed voters the real decision makers. It’s not that they vote literally randomly but they vote based on frivolous reasons that approximate a random vote in the aggregate. Meanwhile, the rest of the 10% of voters are voting based on actual knowledge of the candidate, policy positions, etc. This result, the 10%, makes everything look almost as if 100% of the people were informed voters and is referred to by Caplan as the “miracle of aggregation”.

This depends on the idea that voters (the ignorant ones, that is) are making random rather than systematic errors. The trouble is they do make systematic errors on important issues, namely the economy. Voters in the US are consistently biased about economic issues in ways that economists themselves (right and left) are not: that foreign aid hurts our economy, that budget deficits make a big difference, that immigrants are hurting the job prospects of everyone else, that free trade is bad, etc. The public, in short, has a terrible understanding of one of the most important functions of the national government, managing the economy. That understanding, furthermore, does not manifest as random ignorance but rather as systemic bias. On the economy we do not get the benefit of the miracle of aggregation because ordinary people, for one reason or another, have taken the path of manifestly wrong belief.

Our information network can help mitigate the issue of systemic bias by more clearly identifying and debunking false beliefs. The beliefs mentioned above are well-entrenched and not, generally speaking, discussed openly. Furthermore it is difficult to challenge a well-established belief by attempting to directly argue someone out of it. But an ambiance of inquiry and challenge to all beliefs, which we can foster, should help inculcate in users the habit of questioning long held ideas. Ratings for bias and graphical rollups of bias/informational quality can help, such as this interactive media bias chart. Again, the environment we are building will enable exploration and thought by presenting a whole spectrum of opinion.

On campaigning for elections, specifically, our system can help avoid bias by tying candidates strongly to the information system itself, which rewards substance and integrity. A candidate who presents himself for office will likely already have a reputational score within the system which will weed out not only low scoring candidates but also newcomers who do not have a track record. Needless to say, candidate positions on issues will be vetted through the same system which will tend to keep them honest. The system will not have “TV ads” so candidates will be less likely to gain from producing slick but unsubstantiated attacks on their rivals. The system will also work to mitigate the “filter bubble” effect of social media discussed last time.

Another idea in this vein is “argued voting”. That is everyone who votes must also give an argument for their vote to prove they know what they are doing. Of course, the voter might argue based on a bias, but this is not as likely when the very system we are designing will counteract bias. In other words, a biased argument will likely not be made as much and, if it is, will likely receive a poor rating. The poor rating can then either stand on its own (as a preventative measure for future bad arguments) or serve in some way to influence the vote count (eg 50% argument scores count for half a vote).