More actions

Main article: Ratings system

Debate is a discussion between two or more parties intended to resolve, or at least make clear, differences over a contentious issue. Debate is an important tool of persuasion and truth-finding. We often look at it as a contest but its main purpose is to clarify thinking.

Most debates are informal and unscored. It isn’t really clear who “won” and often both parties come away believing themselves to be the winner. But regardless, the parties also tend to come away with an appreciation for what the other side has to say and why they believe as they do. Debate is an efficient information exchange mechanism.

But while it may enlighten its participants, debate often fails to persuade them or even to establish the truth. Verbal debates, given their informal nature, are generally inconclusive affairs. It would seem we need to rethink debate design and find a mechanism that works better.

The main problem with debate is that it is usually short, verbal, and comes to an end. The quest for truth does not confine itself this way. Just look at the scientific process. In many ways it can be seen as a debate since there are usually promoters and detractors for any new theory. Establishing the truth and persuading the detractors takes years. It is done through academic publications and real experimentation. And it is open-ended. There is no point at which a theory cannot evolve further or be dismantled altogether. Even when we settle on certain “laws” (eg classical mechanics) we leave open the possibility that new experiments might call it into question (eg relativity).

With this in mind, debates should be written and not have short-term time limits imposed on them. Verbal debates are fun to watch but introduce too many confounding factors, such as personality of the debater, speaking style, wit, etc. These may be important characteristics of people, but they don’t really pertain to informed debate. Verbal debate, furthermore, is prone to devolving into tit-for-tat arguments that get lost in the weeds. Writing certainly does not preclude low quality debate but it works against it. Writing also provides the ability to judge the debate in a more dispassionate way.

Written debate formats should allow people to evolve their arguments over time, as their thinking changes and is sharpened by the opponent. This is the purpose of debate and we should enable it through appropriate design. An effective format might be to hold the debate over several levels. The first level would be more of a brainstorming session where arguments are made and responded to. A few exchanges of statement and rebuttal could follow. This level could be unrated, existing as a type of sandbox where debaters can try out ideas without really committing to them. This allows arguments that have no merit to be recognized early and properly discarded. At some point, if the sandbox is successful, the debaters enter a second level where the debate is held again, but this time with the benefit of practice at the first level. A debater who had an effectively rebutted point in the first level can either avoid the point or modify it to meet the objections of his opponent. This second level debate would also go on for a number of exchanges and be rated by the community. More levels of debate could follow where debaters revise their arguments in light of their opponents’ arguments and the ratings they receive from others.

Community involvement in the debate is crucial. It is, after all, the community that will be settling the results of a debate through public policy. It is also the community that can decide whether a debate continues to advance through more levels or has been exhausted and needs to end. For tough issues, the community may decide to leave the debate in an open-ended state or extract certain points from it to act on but otherwise leave the debate to continue.

Debates should be encouraged to get to the essence of their case rather than waste time pursuing tangential points (as so often happens). This is another reason why rating the debates is important. The raters can keep debaters on track or suggest that they take up another topic to debate. The role of raters is flexible. Some raters may want to participate in the debate and form a team with the lead debater. Some may only want to provide advice. Community involvement in debate is generally a good thing and should lead to more democratic decision making.

The multi-level debate format proposed here is only a basic structure. Further rules can be imposed such as the number of exchanges permitted within each level or the type of argument expected (eg opening statement, rebuttal, close). A maximum length might be imposed on each argument although we generally want to allow a great deal of flexibility here, generally in proportion to the complexity of the subject. A fact-checking session might be imposed on all arguments, one in which research is conducted and reported on before debate resumes. This would be another way of allowing debaters to revise their arguments if they prove to be shaky on factual grounds.

Debate Design

Debate Structure

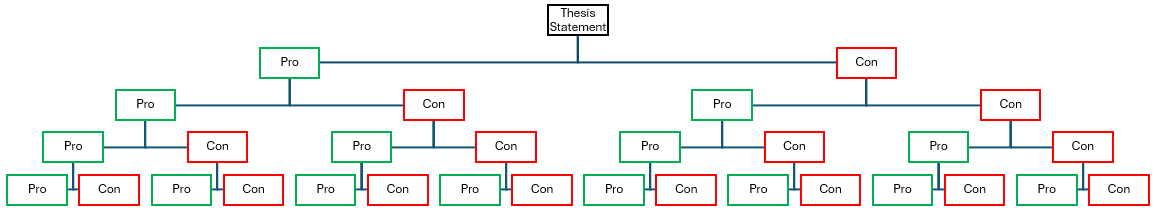

Most of our debate ideas so far would be designed as a tree structure where users can add any number of sub-arguments on the Pro or Con side. The Pro side is colored green and Con side is colored Red, ie:

So far we have implied that the tree can expand without bound but this is not necessarily true, or desirable. A number of options exist which we will touch on here.

Unlimited Debate Tree

In this format, anyone can introduce sub-arguments and the tree the tree can expand without bound:

- Arguments tend to be succinct and of low quality. Kialo, eg, is a good example of this. - Is difficult to visualize in its entirety. Geared toward the content producer rather than the reader.

Limited Debate Tree

Here the tree cuts off at a fixed number of levels and/or sub-arguments per level.

- The number of slots is fixed. Once they are filled, no more can be added. - Has the benefit of easy visualization. - Probably tends toward more writing per argument.

Strict Debate Format

Similar to limited but following an established set of rules, eg NDT (National Debating Tournament), Parliamentary, etc:

- Reproduces oral debating formats (eg opening statement, rebuttal, closing stmt).

- Easily understood by debate enthusiasts.

- Easy to visualize.

- Focuses attention on higher quality arguments.

- Includes rules like no new arguments in the closing statements or rebuttals which keeps the argument organized.

- Has established scoring criteria, although these are tailored to oral debate. For example, if

is the Score for an initial/main argument

is the Score for a rebuttal/reply argument

is the Score for Content

is the Score for Style

is the Score for Strategy

then

for

where .

So initial/main arguments are scored out of 80 and rebuttal/replies are scored out of 40 where Content, Style, and Strategy are weighted at 40%, 40%, and 20% respectively.

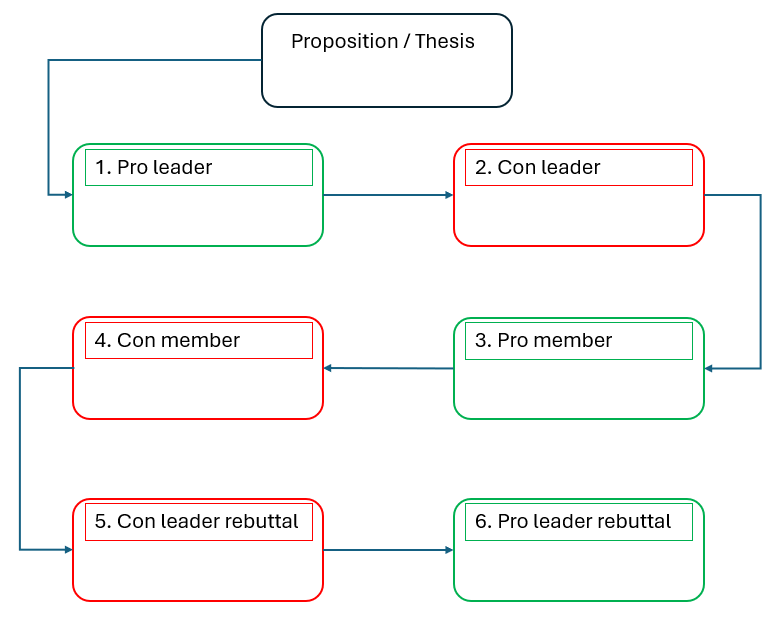

As an example of a strict debate format let's sketch out the Parliamentary debate:

Each side (Pro or Con) has 2 debaters, the leader and the member. The order is as indicated by the arrows although this is obviously for oral debate. In our case, the order could be preserved for an initial round but then more flexibility allowed for changes.

This debate format (like all the others) is simple and is very restricted as to the number of slots allowed. It may be necessary to modify this to allow more slots to engage more participants.

Allowing Changes

For all the formats, the issue of how, and whether, to allow changes needs to be addressed.

Some thoughts on not allowing changes:

- It would have the benefit of simplicity. The arguments that have been made are static. The argument can only get bigger and would simply expand to lower tree levels.

- Favors the unlimited debate structure. Someone can always provide a sub-argument for any argument that gets made.

- Would encourage people to carefully word their arguments up front.

- Any rewording or clarifications would themselves have to be sub-arguments.

- Scoring would get complicated since revisions to arguments made below the original argument would be mixed together.

- Following the argument might be difficult because revisions to arguments that get posted as new sub-arguments would not be clear as to what they really are.

- Has the major disadvantage of not allowing the argument to mature and improve over time.

Some thoughts on allowing changes:

- Promotes the idea of quality argumentation as feedback is obtained and authors have time to reconsider their points.

- Arguments would be more consolidated and less fragmented. We generally want our arguments to be relatively complete essays, not a bunch of single phrases that readers have to piece together.

- Favors the limited debate structure.

- Once authors make changes, other participants will need to be alerted so they can make changes too if necessary (ie to sub-arguments). Scorers will also be alerted so they can revise their scores.

- Owners should be able to concede by marking their arguments as such. This could happen if a sub-argument is made that invalidates their argument. Conceding would leave the argument visible but in an inactive state so other participants know it is no longer being advocated for. New sub-arguments could still be made, especially ones that cause the concession to be revoked.

- A history could be maintained so that the reader can click through a timeline of the argument, as each change is made. Users should be able to do this with the whole tree or a sub-section of the tree, or a single sub-argument.

- UI idea to reduce clutter: Only show the highest scoring arguments / sub-arguments at each level.

I'm generally in favor of users being able to change their arguments. Static arguments will lead to complex looking trees which are hard to read. Besides, it seems unreasonable to lock an argument down once an author has published it. Since we're aiming for high quality, the idea of being able to edit makes sense. Although in verbal debate you can't take back what you said, you should be able to in written debates. Our system should provide for that.

Who gets to debate?

In the unlimited debate discussed above, anyone can participate. However, in any of the limited debate formats there will be a fixed number of "slots" for each debater. How to allocate the slots will be an issue. Various arrangements might exist for doing that:

- First come, first served.

- First come, first served if participant has a score above a certain level. We generally want to encourage the "good" debaters to come forward.

- Competition for each slot. A competitive round takes place with each candidate presents their argument. The highest scorers take the slots.

- Team debate. A group of users is formed which takes on its own identity and is scored separately. Like a debate team in high school or college. The group would have its own trust and private discussion section to hash out arguments collaboratively.

- Delegated debater. A group of users elects a debater who debates on their behalf.

- Anyone can join but low scoring arguments are thrown out. Ie everyone can compete for the slot but only the highest score wins.

For our purposes the best system for assigning debaters is probably to allow for competition for each slot. This gives us the best chance at quality and also gamifies the system to some extent. A variant on this would be allowing losing participants to form a team with the lead debater (the guy who won the slot).

Regardless of who gets to debate, a comment section should be open to all users. Commenters could influence the debater to change their wording, introduce ideas, etc. It would be similar to the comments section in Kialo. Privacy settings could be enabled which allow the section to be used for closed-door discussion by, for instance, debate teams.

Scoring Thoughts

Instead of using a rolled up argument score, discussed previously, we could simplify the system and have everyone rate each argument and sub-argument individually. A mechanism to allow scoring of the entire Pro and Con side of the argument could also be created.

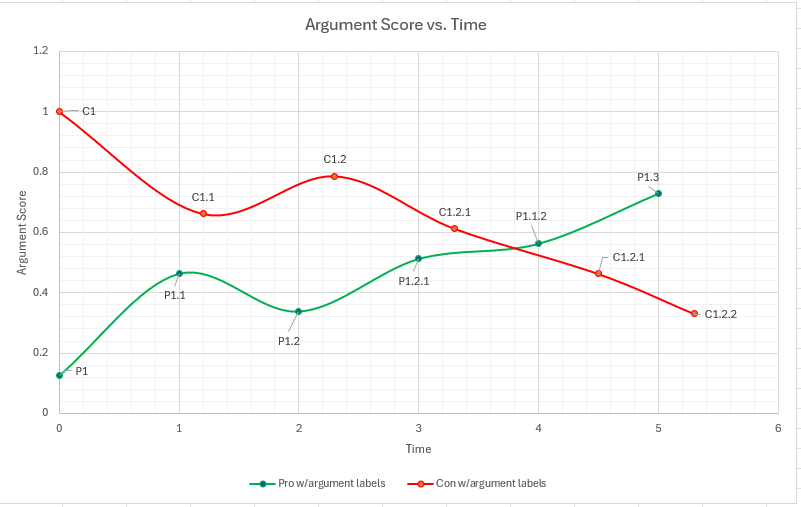

A system to keep track of the time when arguments are made and when scores are given would allow us to track the history of arguments and provide insights, such as which arguments are having the most impact.

In the following hypothetical figure, the entire Pro and Con side score is shown as a function of time. The labeled markers show the argument that was made most recently corresponding to the score.

The markers could also include a group of arguments made recently that would have given rise to the increase/decrease in the score. The ability to click on the argument in the chart and visualize the text might be an added enhancement.

More on scoring of practical arguments

Practical arguments will be important in community policymaking and one way of scoring them is by using the $Cost \over Benefit$ ratio. Another related idea is to assess the probability of the scenario in question. Scorers would then rate the argument for a proposal on its cost, benefits, and probability of occurrence.

It might be easier to think of cost-benefit in terms of return. One simple possibility is:

Another is the more traditional return on investment:

These have the advantage of clarity since positive numbers are good and negative numbers are bad. They also do not lead to infinity when the benefit is zero.

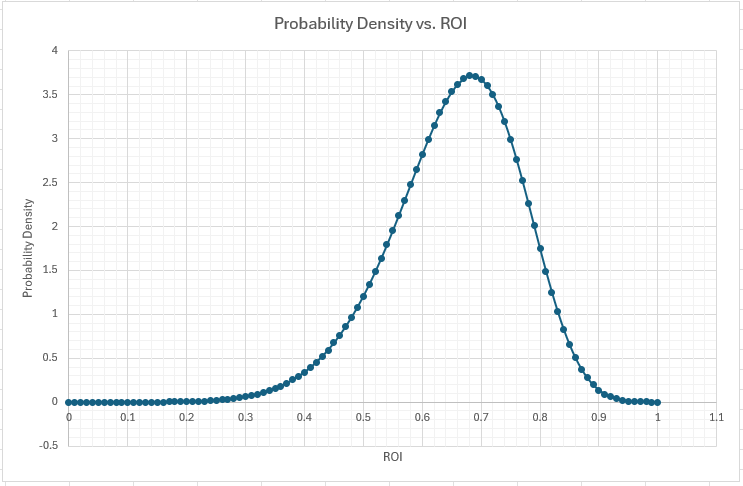

Given enough scoring input we could envision a PDF of a scenario under consideration:

Other such PDF's would be generated for each different scenario. Decision makers would then have a ready tool for evaluation purposes.

Along these lines, it would be nice to have a single rolled-up measure of goodness which combines Benefit, Cost, and Probability. Various ways to combine these might be formulated, the simplest of which might be:

Then decision makers can evaluate the highest $G$ proposals since they are presumably both likely and have a high return. In practice, however, this is difficult to do because we don't know the relative importance of each contribution. In our case we are not just considering standard business investments. We also have to consider arguments in which we want to avoid (at any cost) low probability bad outcomes, like nuclear war. Suppose we were considering becoming directly involved in a far-off war. There's a reasonable probability of success with a high ROI but a small probability of nuclear war. This alone would preclude further consideration of such a policy. For general cases, it seems more reasonable to present return and probability separately and allow decision makers to sort it out.

Gamification

The system should be gamified to provide an additional incentive to participate and produce quality arguments. Arguments will be scored on rhetorical and practical quality as discussed previously. Participants can then also be scored, obviously, from the average of their argument scores, either rhetorical or practical or both. A ranking system will provide ambitious debaters with a clear goal.

Highly ranked debaters can also be given privileges, such as easier access to slots in limited debates (as discussed above), higher voting power, the ability to propose specialized debate formats, etc.

Since the ability to score the entire Pro and Con side of the argument will be available, prominently displaying this score on each debate as it progresses will help gamify it. Easy access and visualization of scores for sub-arguments and individual debaters should also help.

A Reasonableness Score?

Debate, like sporting events, is designed to produce winners and losers. That's part of its appeal and central to gamification. But alot of debate is an attempt to obtain compromise. Our system should enable this by providing a concluding statement that the debaters agree to. No one is forced to do this but if they do, they would be scored on an additional measure, "reasonableness" or "willingness to compromise". A debate between theists and atheists might provide a concluding statement that "Although there is no way to explicitly demonstrate God's existence, everyone's lived experience on this subject should be respected." This doesn't say much but it at least gives users the ability to shake hands and call it a day. Something we don't get alot of in our debates these days. Even a concluding statement that just summarizes the positions is useful in this regard. Incentivizing debate participants to find common ground, if only symbolically, would be useful in reducing polarization and extremism.

Creating a new argument from an old one

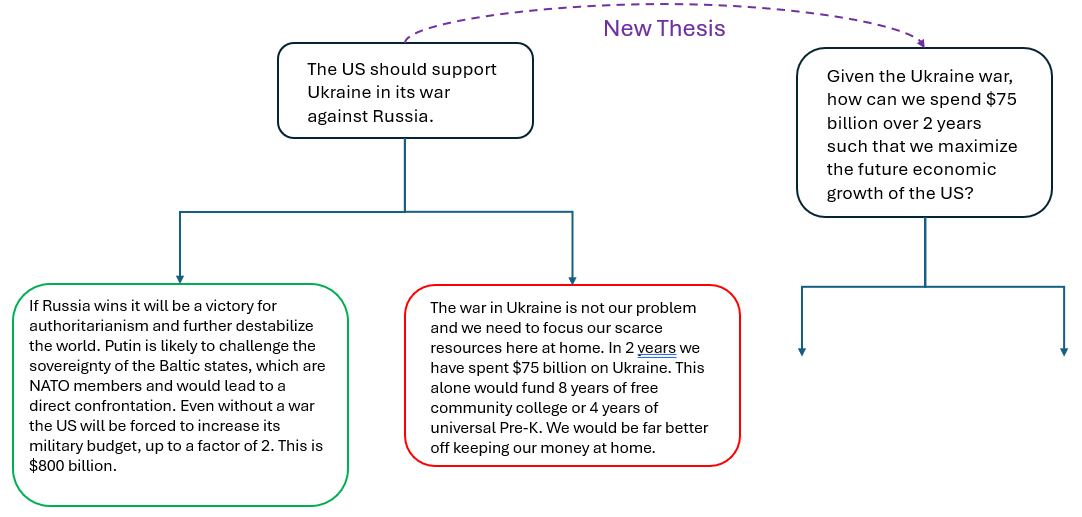

Let's suppose we've been engaged in an uproductive rhetorical argument and want to convert it into a productive practical argument. The unproductive argument might be viewed as a tree and we might think of the new argument as simply an extension to the tree below it. However, instead of doing this, we could simply create a new argument from the top and link it to the old thesis statement. Both arguments will then appear side by side:

The original debaters would propose tabling the old argument and moving to a new one. Some type of agreement would need to be obtained to do this but, in principle, it could be done unilaterally by a single debater. Then those who wish to participate in the new debate could do so while those interested in continuing the old debate could also do so. The new argument would be linked to the old one to preserve a historical record, as noted above.

This will be how we change rhetorical arguments to practical ones, as also noted above. However there may be many reasons for moving to a new argument:

- Unclear thesis statement.

- Thesis statement that is not focused enough. Moving to a practical argument is an example of this.

- The need to expand the argument to include other factors. Eg an argument about the economics of AI needs to include moral ones as well.

- A realization that the argument is really about something else. Eg an argument about abortion is really an argument about self conscious awareness.

- A desire to censure the thesis because it is offensive or violates site rules, eg "we should eliminate ethnic group x".

For a new practical argument thesis statement, we will face the need to precisely define the goal. Indeed, a practical argument may face the need to move to a new thesis statement several times as different aspects of a broader goal are considered. In general, the goal will be stated as a value function which can be anything. For the "killing of John" example in [last week's post](Trust in Argument Scoring and Rhetorical vs. Practical Arguments) we could envision the value of saving 5 lives in isolation or with the legal/moral ramifications included. These are two different value functions. The value function will be a cost-benefit-probability statement which is discussed more below. This type of argument presumes that experts will be doing the arguing, another subject taken up in more detail below.

Debate and the Pareto Frontier

Debate should reduce to an exercise in choosing along the Pareto frontier. This is to say that without first establishing the Pareto frontier, a final debate involving policy choices should not begin because it will more than likely involve dominated alternatives. Once the Pareto curve is understood, the debate can proceed to the somewhat more subjective matter of choosing a point on it. For instance, a community may be choosing between supercomputer designs and has a Pareto front with Performance vs. Cost. The choice boils down to how much they want to pay for each level of Performance. The stage has thus been set for a productive debate.

This is an example of getting to the crux of the argument, an important property that debate should bring out or, in this case, start with. All debate should ultimately try to find the Pareto frontier and then choose from the points along its curve.

This idea should apply even for more abstract and contentious issues, such as abortion. The abortion debate often revolves around when life begins. The pro-life movement believes it begins at conception and the pro-choice movement believes it begins, for practical purposes, quite a bit later. However, almost no one in the pro-choice movement thinks that infanticide, right after natural birth, is permissible. Similarly, they don’t believe in abortion the day before a baby would be born naturally. They believe in some range, well after conception and well before birth. The decision of when to draw the line is an example of a tussle along a Pareto curve with only one dimension, the time in pregnancy beyond which it would be illegal/immoral to have an abortion. The pro-life advocate wants that time set to the lowest possible number, and the pro-choice advocate the highest possible number without going over some limit. Once the debate reaches this point, settling it becomes a subjective judgement or simply a practical compromise dictated by political considerations. Further debate is pointless, without new evidence, since we have succeeded in finding the “Pareto curve”, simplistic though it may be, and have identified the crux of the argument.

Note that the abortion debate relies heavily on our knowledge of the fetus. If a fetus is found to have surprising cognitive abilities, for instance, the pro-choice advocate would probably agree to move the permissible abortion time to an earlier point. This means that changes are possible to a settled debate but only with new information. Incidentally, this is one reason the pro-life movement has been so successful of late. Through better imaging of the fetus they have found medical evidence suggesting that fetuses develop critical functions (like a heartbeat) earlier in pregnancy than was once thought.

Communities, along these lines, might stipulate that once a policy is enacted post-debate, it cannot be changed without substantial new information. That is, debaters are not allowed to continue arguing settled issues. Since there will be no law (hopefully) preventing debate in these circumstances, ratings themselves will have to perform the work of shutting down repetitive arguments and argumentative people. An unrated sandbox, as noted above, will always exist where people can argue for its own sake. One idea might then be to take unending debates, relegate them back to the sandbox, and stop providing them with new levels.

The abortion debate can be more sophisticated, of course, than simply the time at which life begins. Let’s suppose that, as a result of the debate above, we have passed a law that outlaws abortion after 18 weeks of pregnancy.

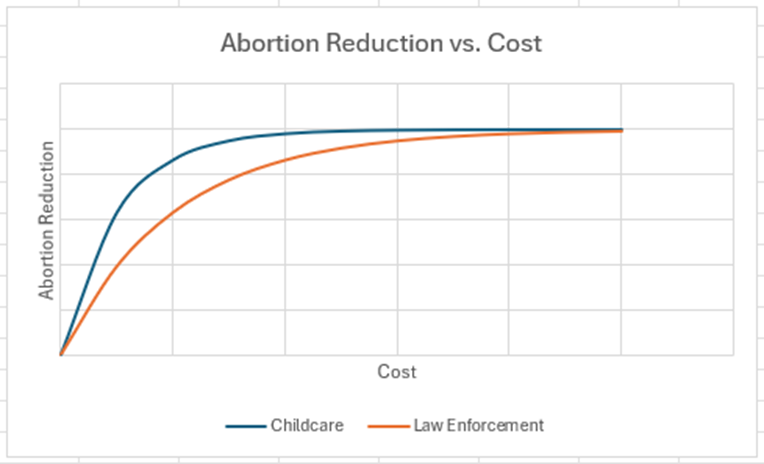

The debate can now move on. We could introduce a two-dimensional objective function by considering policies that result in more or less abortions. Presumably we would want to reduce the number of women who seek abortions in the first place, whether legally or not. A policy that gives women support for childcare, for instance, might be put forth on the grounds that it will remove the financial incentive to have an abortion. We can contrast that with a policy that, say, steps up enforcement of the abortion ban after 18 weeks. So, we have two policies and two outcomes. Both of these would have their own cost-performance Pareto curve which we might plot as follows.

Here the childcare option dominates the law enforcement option and should be the selected policy. There is simply no mechanism of law enforcement that is more effective at all cost points. Keep in mind here that the law enforcement policy is, by itself, Pareto optimal. That is, it is already the optimal policy in terms of how we should design it (tactics, manpower, budget, etc.). Therefore no one can argue that we haven’t considered some aspect of law enforcement that improves the situation.

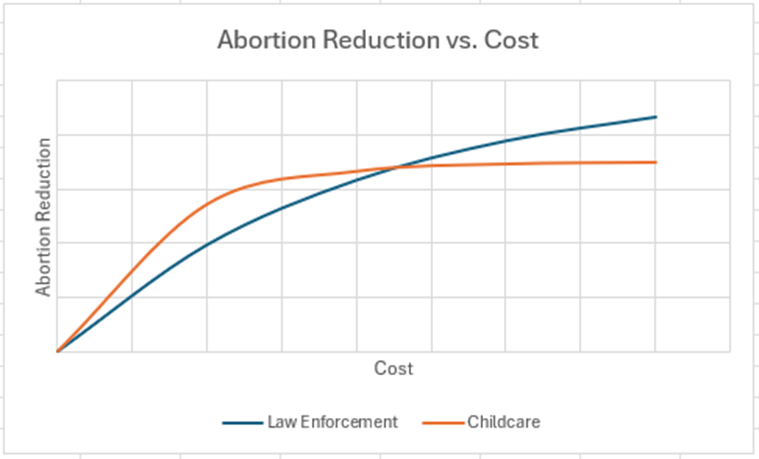

But we might have curves that look like this:

Here we have a cost where there is crossover. One policy dominates below a certain cost and another one above. The community will probably have budgetary constraints anyway, so the appropriate policy can be decided easily. If not we have, again, a subjective judgement to make. But at least we’ve identified the bone of contention.

It is likely that the pro-choice debater will want to argue against the law enforcement policy no matter what because they are against any abortion restriction. But we already have a settled law on the books banning abortion after 18 weeks. The pro-choice debater cannot re-argue that issue without new knowledge. We stipulate, furthermore, that they cannot enter into the new policy debate in good faith by relitigating the old one.

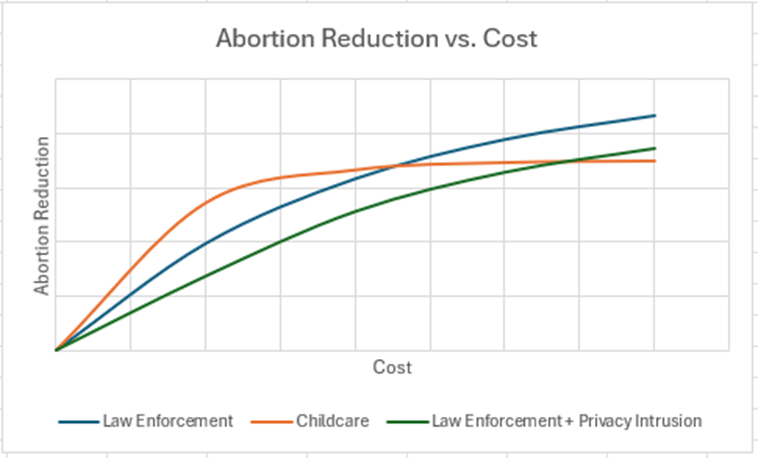

What can be done, however, is to introduce a second independent variable for Pareto consideration. In addition to cost, we might have privacy intrusiveness as a variable to be minimized. This amounts to a new insight, new information if you will. We would argue that, all things being equal, it is better to opt for a policy that minimizes the state’s intrusiveness into someone’s life. Certainly in this case, the law enforcement policy doesn’t look quite as good. We could plot this new variable on a third axis of the graph but then it starts getting hard to capture visually, [as we’ve discussed](Brainstorming_11). A better option might be to combine it with the cost variable. In other words, we’d be looking at cost in terms of the community budget and also in terms of privacy intrusion. This essentially moves the law enforcement cost curve to the right:

With this curve in mind, the community is prepared to make a decision.

Nearly all contentious issues can be reduced in this way as long as the debate stays focused on extracting the crux of the argument and not getting mired in tangential issues. Once the crux is identified, simulation can help produce the actual Pareto frontier curves for use in decision-making. The ultimate purpose of debate is to do this, not provide a forum for rancorous argument or entertainment.

This debate could also veer off into philosophy by diving into the notion of when a fetus should be considered a conscious person, with the legal protections that all such persons enjoy. The pro-life argument is usually religious and precludes any speculation in this direction. But the pro-choice side, by limiting abortion to well before the natural time of birth, might have some ideas about this. Even the pro-life side could jump in, sensing an opportunity to move the upper limit to an earlier point. Such a debate is permissible, of course, but it should be removed from a policymaking arena. It is likely to be inconclusive, as many philosophical debates are, and have an impact only in the longer term.

It is also likely to be held by academics who have advanced training in philosophy. This is not to say that we shouldn’t have such debates. They, like scientific debates, further our understanding of the world. It is philosophical and scientific inquiry that has informed our thinking on matters of animal consciousness, for instance, and shifted our views toward their more humane treatment.

Let’s take another traditional debate that appears to be ideologically driven but is really an optimization problem: how much the government should spend on the poor. Before we start, let’s keep in mind that any argument that invokes personal circumstances should be rejected outright. No one can say “I don’t want my tax dollars to help the poor” or “I am poor so I want that program”. Personal circumstances arguments should be rated by the system as unworthy. People can certainly feel that way, and express that sentiment, but not in a debate that is trying to extract valuable public policy guidance. This, btw, is how Rawls would have it as well, limiting debate to publicly accepted basic principles. There are exceptions to this idea, of course, such as when an individual circumstance serves to introduce valuable public information, eg “the policy, if enacted, would result in my death because I wouldn’t be able to afford medical care”. Generally speaking, however, the personal complaint is not an argument.

We are left with an economics and morality argument. What is the amount of help a society should give the poor to maximize economic performance (or HDI)? At which point does the help become immoral because it provides too little? At which point does it become excessive? These points again, can be reduced to objective functions and analyzed mathematically.

This particular debate is important because it touches on Rawlsian issues of basic liberties. If we do not have enough food, we are not really free to participate, especially as equals, in the workings of society. We aren’t free to pursue an education or the job we want (both Rawlsian rights). So the economics debate about helping the poor is only an exercise in optimization once the moral dimension of the question is clear. If we have decided unequivocally, as a society, that we will not permit starvation then the optimization question becomes a matter of how best to accomplish this. We are no longer debating whether or not to permit it. In a sense, the moral debate, like the “when life begins debate”, is a one-dimensional Pareto curve but this time with a binary choice: whether to permit starvation or not.

A binary-choice debate, such as this, is relatively easy to resolve. A community will debate the matter and will either persuade all its members one way or the other, or create a split opinion. A split opinion would then lead to a vote and a decision rendered. This is straightforward enough with the exception that such a vote (or debate) might be precluded by some sort of higher law (constitutional) which has already rendered a decision. In such a case, we presume the debate is already settled. If members want to change the constitution, the vote would have to be conducted in accord with such an objective (eg require a super-majority).

We might conclude this section by commenting on the rigor advocated here for how debate should be managed. A critic might react by saying that free people should be able to debate however they like. There shouldn’t be rules about how they are conducted or how they end. We shouldn’t be required to optimize an objective function when all we’re trying to do is talk to each other. This is fair criticism. But every polity needs its rules of order. No government can function if everyone gets to speak at once. In a direct democracy, the kind we are envisioning, this is especially true. Of course, people will be allowed to have unstructured debate. The sandbox mentioned above will exist where unrated debate of this nature can take place. But the mechanisms by which policy is decided needs to have some kind of organized approach. The creation of a flexible debate structure, where everyone can participate, but leading to optimal outcomes, should bridge the gap between an overly restrictive system and an unproductive cacophony of arguments.

Debate Effectiveness

Here are some ideas, in no particular order, on making debate more productive and relevant to community concerns:

- Community-based systems shouldn't flip-flop on decision making. We want some sort of hysteresis in the system. Rules of order are also necessary to prevent debate from continuing indefinitely and, once decisions are made, not revisiting the subject until truly new information becomes available.

- However, we could let debate continue and just have a filtering mechanism to allow people to ignore it. This, less forceful approach, is preferable to cutting debate off. There should always be a place where people can debate, whether rated or not.

- We need to have more, not less, philosophical debate (eg see abortion debate above). Abortion is contentious mainly because of philosophical (or religious) concerns. Since we’re trying to turn people into policymakers, we might be also successful in turning them into philosophers. Philosophical debate (and scientific debate) is the driver for most of the changes that take place in our thinking.

- Debate structure should be tuned to its purpose. A regimented structure might be necessary for formal policymaking. A looser structure might be ok for philosophical debate. Scientific debate, in turn, might need something in between.

- We could use AI to help debates remain civil and detect when they are degenerating into chaos. An "AI-ombudsperson" could intervene in cases where the debate is becoming unproductive.

Debate is closely related to argument evaluation and scoring.