More actions

Main article: Ratings system

Our current society is filled with various types of rating systems. Some are ratings by experts or users of products and services. Consumer Reports is a well-known example of this. Online retailers like Amazon and Walmart have user-ratings to accompany almost every product they sell. Online forums where individuals can post their advice are also rated so you obtain the highest rated posts at the top, eg Stackoverflow. Ratings for larger institutions also exist, such as for hospitals and universities. Usually these are provided by experts with contributions from ordinary users. Others are ratings for entire countries, such as Freedom House.

Here we will take a look at a few of these.

Freedom House

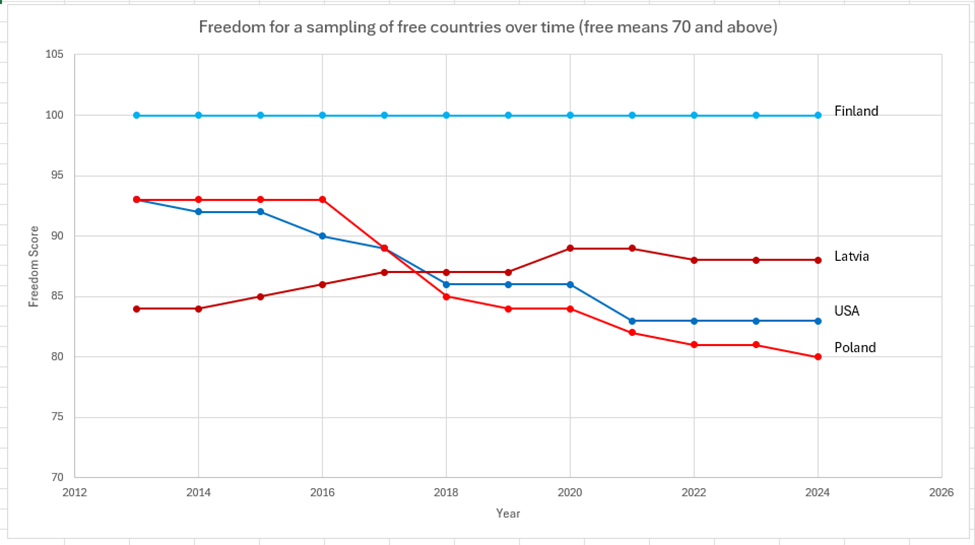

Last time, we saw the not-great performance of the US on the Freedom House scores. One question was how the US did over time. The following shows a sampling of “free” countries and their performance since 2013:

As we suspected, the US has declined significantly since the advent political polarization and extremism. It looks like Poland has had a similar trajectory with the rise of its own form of the same. Meanwhile Latvia, after several years of improvement, declined modestly from 2021 to 2022 and has been steady since then. For reference, we include the top country, Finland, which has achieved the highest possible score throughout this period. No other country has quite matched Finland but the other Nordic countries are very close, as are Canada, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Australia, and Japan.

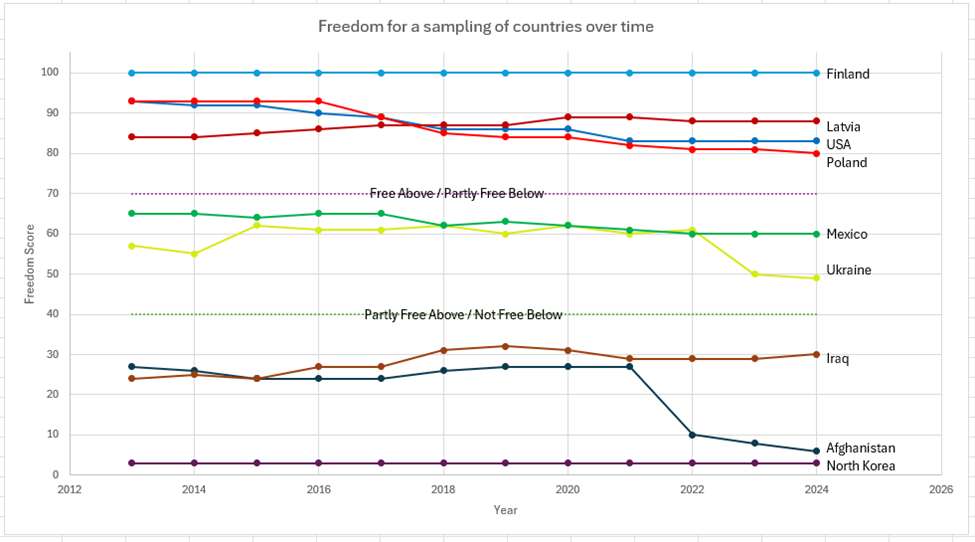

Here’s a chart showing, in addition, a few countries that are not so free:

We might conclude that North Korea is the worst country on freedom but there are a few lesser known countries (Turkmenistan, South Sudan) which score even lower. But at this point the differences are small. North Korea gets a 3, Turkmenistan a 2, and South Sudan a 1 (in 2024).

We should note here that freedom is a function of both government and private repression. In North Korea the government is very strong and repressive but private repression is low (there is little to no crime in North Korea). In South Sudan, however, the government is weak but private actors (criminals, warlords, private armies, terrorists) conspire to create a repressive and unsafe environment. This situation creates a vicious cycle: the lawlessness itself reduces freedom, and the government’s response to it, often ineffective, further limits the freedom of ordinary citizens.

The other two countries, Iraq and Afghanistan serve as a reminder to Americans of how badly those two wars went. If their purpose was to create stable democracies in the middle east, they were utter failures. Afghanistan ended with a victory for the Taliban, at which point a sharp decline from bad to worse ensued. Meanwhile Iraq has hovered in democratic mediocrity for years. Perhaps the only positive point here is that Iraq was even less free under Saddam Hussein. This was not shown here but a different dataset, going further back, confirms it: Country_and_Territory_Ratings_and_Statuses_FIW_1973-2024.xlsx. We might deem this a “worse to bad” progression.

We might also notice the highest rating, for Finland, and ask whether the methodology grades on a curve. Freedom House claims to be objective and uses a wide variety of categories to arrive at the aggregate score. Nevertheless, it is fairly clear that an implicit curve is built in. Not to take anything away from Finland, which is by all accounts a stellar example of democracy, it is not a perfect Rawlsian society. The government, while clean by world standards, is not entirely free of corruption. There is some crime as well as significant racial/ethnic bias in hiring, even though the country scores comparatively well on both. Taxation is quite high although, given the excellent level of social services, Finns are arguably getting what they pay for and choosing to pay. Nevertheless, taxation is always form of government imposition. So, a 100? The country isn’t perfect, so probably not. It might be hard to get better than Finland but that just means Freedom House is, obviously, grading on a curve.

Our ratings system should preclude curve-style grading because it leads to a sense of complacency and obscures problems that could be worked on. This is true for both societies and individuals. In the Finnish case we might want to accurately quantify any crime, corruption, lack of transparency, bias, etc., low though they may be, and use them as the basis for a truly objective aggregate.

We might notice, quite obviously, that Freedom House is a ratings system for countries. We’ve discussed how different communities will no doubt choose to interact with each other based on a similar system, that is their assessment of how well their peer communities hold up values of importance to them. Our ratings system is one for not just individuals but the entirety of a community. A community, in this instance, may rate itself and be rated by other communities.

Will any of this motivate communities to improve? Does the fact that the US freedom rating has declined steadily for several years motivate us to improve? Not many Americans know about Freedom House but we have a general sense that democracy is backsliding in the US. This may not matter much to Americans but let’s keep in mind that the rating system in our new society will be front and center. We are proposing a society in which ratings are a continuous presence in everyone’s life and the presumption is that we will take them seriously. After all, they will determine our standing in society and the fruits of economic distribution. It would seem that a society tuned in to ratings on an individual basis would also be concerned about how their community fares vis a vis other communities.

This is not just wishful thinking on my part. The US is a bad example of the effect of ratings since many Americans are simply indifferent to how the world views us. But if we travel to smaller nations, one’s more dependent on trade and productive relationships with the rest of the world, we find their citizens far more aware of how their society is viewed by others. Our communities will also presumably be small, smaller than nations (we think), and should have a healthy regard for how they are perceived by other communities.

Still, a plethora of ratings information can be information overload, and many people will probably not be interested in how their community ranks on democracy. They will be even less interested in rating other communities. But organizations like Freedom House can exist to both provide ratings and distill them into politically actionable recommendations. Individuals can delegate their ratings power (weight) to organizations such as these who will provide this service for them. It is easy to imagine how a large number of such organizations could exist for various issues.

In this sense, our direct democracy would evolve into a more representative one. This is probably inevitable but it would be quite a bit different than what we have today. The delegation of ratings power to organizations would be done by individuals when and if they want to and can be taken back at any time. Also note that such a delegation would be done to not a single representative (or political party) but to any person or organization who, presumably, demonstrates expertise in a certain area. This would lead to “representation” by knowledgeable people rather than politicians who have little expertise in complex policy issues.

We have done this to some extent with Freedom House itself. We might have some notional understanding of how free different countries are around the world, but we lack detailed knowledge on every country. And we generally lack the specifics that are important to numerical ratings. Just how much does Viktor Orban’s Fidesz party control the media in Hungary? How much is personal freedom impacted by criminal organizations in Mexico? How much has our judiciary degraded fundamental rights in the US? It is hard to answer these questions precisely except by doing a comparative analysis and getting some training in assigning numerical scores to issues that have a heavy subjective bent. Not to mention having the time to go through a long list of countries and the multiplicity of factors that influence freedom. Organizations like Freedom House have the staff and support structure to carry out these types of analyses, whereas individuals usually do not.

Why do we think Freedom House, in particular, is trustworthy? Well, it appears to be non-partisan, draws its leadership from a diverse group of ex-government, business, and media officials. It posts the bio of its analysts on its website and they seem to be qualified. It has a long history (founded in 1941) and seems to be an established, well respected organization. It has been used widely in the media and by the US government for information about democracy in other countries. It has, however, been criticized for being US-centric and its ratings tend to be in line with US foreign policy. This Washington Post article singles it out for some criticism along these lines:

Notably, the article also mentions that in its early years, its ratings were the product of one person and his wife, who acted as his assistant. This person admits that some “guesswork” went into them. Nevertheless, it has improved its methodology over the years and is a respected organization. It’s ratings, incidentally, can be compared to other similar organizations, such as the Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index:

https://infographics.economist.com/2017/DemocracyIndex/

In general, these ratings are roughly in line with Freedom House’s. In any case, any system of ratings that we “delegate” to will itself be subject to the public’s ratings. If Freedom House is considered biased, as that Washington Post article alluded to, we would presumably have sources to tell us that (ie the media). A virtuous circle of ratings presumably keeps everyone honest.

In any event, our communities will no doubt have organizations to perform as specialized ratings services. Members will delegate their rating power to them, if they choose to, creating de facto representative bodies. We might look upon this “erosion” of direct democracy with dismay, but we should note that it is probably natural and inevitable. According to Chandler, historians estimate that of 30,000 Athenian citizens, only about 1,000 were actively engaged in politics and only about 20 initiated most policy. In other words, a political class of informal representatives arose naturally.

The Chinese Social Credit System (SCS)

This brings to mind the notion of government-controlled ratings systems, such as the social credit system (SCS) in China (see https://velocityglobal.com/resources/blog/chinese-social-credit-system/ and https://joinhorizons.com/china-social-credit-system-explained/). The SCS has its roots in Chinese history and culture dating back to Confucianism, a philosophy which emphasized the relationship between individual character and the functioning of society. But China’s current system was inspired, in the 1990’s, by the financial credit rating system in the US, and for many years its purpose was essentially just that – financial. They wanted to develop Western style financing and needed a way to establish trust in a country where fraud and cheating were common. They extended this to businesses with the purpose of inducing greater trust in Chinese companies that Western firms were considering collaborating with. Today, although its emphasis is still financial, it has been extended and grown into a complex system of behavior modification.

It measures such activities as paying taxes on time, reporting financial data accurately, staying out of legal trouble, donating to charity, taking care of family members, helping with community activities, etc. Individuals who perform well get put on “redlists” which give them easier access to credit and other benefits. Those who don’t, get put on “blacklists” which limits their ability to find jobs, places to live, travel, etc. The system is applied to individuals, businesses, and government officials (ostensibly to reduce corruption). For businesses, complying with government regulations is an important criteria in the aggregate score they receive. The system has grown more centralized although data that is collected comes from many sources throughout the country.

Needless to say, this system isn’t popular in the West because it is associated with big-brother style surveillance. Nevertheless, we might want to stop and think about it for a moment. We might ask why a country would expend large amounts of resources to develop such a system. It must have some positive benefit, right? In addition to compelling good behavior of its citizens, the presumed “benefit” is ensuring political harmony, that is harmony with the CCP (Chinese Communist Party). Westerners may turn away from motivations like that but isn’t political harmony generally a good thing? Isn’t that what we lack right now and need more of in the US? Didn’t we have that in years past when we were defined by two political parties (not one as in China) that were much closer together, one center-left and the other center-right? Didn’t our media and social environment conspire to create a system of relatively harmonized politics? We may not have had Chinese style surveillance but we did have a propaganda mechanism that defined, quite sharply, acceptable political boundaries and behavior. And, in terms of compelling good behavior, many Western analysts have noted the parallel between Chinese surveillance and the rising surveillance in our own societies brought on by technology.

Along these lines we may want to compare and contrast our own ratings system with the Chinese SCS. We should start by first noting that many of our aims are the same: we want better societal behavior in general and, more specifically, an avoidance of destructive ideological/political polarization. We envision, despite political differences, a relatively harmonious society that hews to facts and the truth. This is perhaps the first important contrast: The SCS is designed to further the political agenda of the CCP and ours is to find an optimized political agenda based on objective reasoning. There is only one party in China (and only two in the US) but there can be several in our system. Indeed we envision many diverse political communities and diversity of thought within each individual community.

Another big difference is privacy. The SCS appears to lack privacy controls to the extent that it is probably a detriment to basic liberties. The SCS vacuums up everyone’s data and sends it to government agencies which work out aggregate scores. There doesn’t seem to be much anyone can do about this. Mistakes are difficult to correct and punishment can be quite arbitrary. There are stories of Chinese citizens suddenly finding themselves on blacklists in the middle of a trip and then having no way to get home (one of the punishments is to lose access to rail and air tickets).

The other glaring difference is the top-down nature of the SCS vs the bottom-up nature of our ratings system. One of the primary reasons for our system is to enable democratic participation. Its central function is to allow people to regain power from established institutions and impersonal forces, such as the “market” which conspire to advance the agenda of the few, to the detriment of the many. The SCS has no such purpose.

Let’s pause for a moment and highlight some of the important differences between the SCS and our ratings system:

- Unlike the SCS, our system is ultimately controlled by members of the community, not a faceless central government. Even though organizations may perform ratings, they will be subject to other organizations’ control and the people.

- In particular, the privacy of the system will be controlled by individuals and the community at large (more on this later).

- Sanctions due to low ratings, or rewards due to high ratings, will be subject to community approval and closely supervised for fairness.

- An unfair rating due to, for instance, a personal vendetta can be challenged in “court”. The rating will be removed if the aggrieved party is found to be right. If the rating is the product of malice or some other self-interested reason, the rater can be sanctioned.

- The ratings methodology and algorithms are subject to continuous community review and modification.

- The ratings system itself is a voting system which inherently allows community participation in policy-making activities.

One interesting aspect of the SCS is the blacklist/redlist system. This might seem dystopian, as many aspects of the SCS are, but there may be a way to apply it constructively and in a way consistent with basic liberties. Our ratings system already has the notion that people will receive a higher income (or more goods/services) as a function of their rating. So this is similar to the Chinese redlist. We would emphasize that such a system should allow for modest income graduations, consistent with Rawls’ difference principle, and to avoid the development of privileged classes. The blacklist is more problematic but we might set some lower ratings limit and blacklist people who fall under it by removing, for instance, their right to privacy. The low limit would be very low, for example conviction of a serious criminal offense. In a sense we already do that with our ability to publicly check anyone’s court records, as noted above.

This brings to mind the notion of flexible privacy rights. We might envision, for one, a privacy difference between organizations and individuals. Organizations would not have any right to privacy given their greater capacity for malfeasance and the fact that no individual basic liberty seems to be at stake in holding them to complete transparency. Obviously for individuals, this is different, but we might also consider the idea that increased trustworthiness allows for increased privacy rights. Instead of the blacklist mentioned above, we could have a system where folks give up privacy rights along some sliding scale as their trustworthiness score decreases. Needless to say, any move to take away fundamental rights according to some algorithm brings to mind dystopian visions, so this would need to have a sizeable benefit compared to its obvious risk.