More actions

Created page with "<h2>The Philosophy of John Rawls</h2> It is not for lack of ideas that the US finds itself in its current predicament, a brilliant but declining superpower hobbled by entirely self-inflicted wounds. [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/rawls/ John Rawls], perhaps the most influential political philosopher of the 20th century, laid out some basic ideas, broadly known by the term “justice as fairness”. He describes a methodology by which we can objectively find how soc..." |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<h2>The Philosophy of John Rawls</h2> |

<h2>The Philosophy of John Rawls</h2> |

||

[[wikipedia:John Rawls]] is considered the most influential political philosopher of the 20th century, on a par with Hobbes and Locke. |

|||

It is not for lack of ideas that the US finds itself in its current predicament, a brilliant but declining superpower hobbled by entirely self-inflicted wounds. [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/rawls/ John Rawls], perhaps the most influential political philosopher of the 20th century, laid out some basic ideas, broadly known by the term “justice as fairness”. He describes a methodology by which we can objectively find how society should be organized. His principles are classic Western liberal ones of freedom and equality. We might think these are coherent with our foundational principles but in fact the US has diverged significantly from them, a subject we can discuss another time. For now let’s turn to Rawls’ philosophy. |

It is not for lack of ideas that the US finds itself in its current predicament, a brilliant but declining superpower hobbled by entirely self-inflicted wounds. [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/rawls/ John Rawls], perhaps the most influential political philosopher of the 20th century, laid out some basic ideas, broadly known by the term “justice as fairness”. He describes a methodology by which we can objectively find how society should be organized. His principles are classic Western liberal ones of freedom and equality. We might think these are coherent with our foundational principles but in fact the US has diverged significantly from them, a subject we can discuss another time. For now let’s turn to Rawls’ philosophy. |

||

Revision as of 20:16, 27 August 2024

The Philosophy of John Rawls

wikipedia:John Rawls is considered the most influential political philosopher of the 20th century, on a par with Hobbes and Locke.

It is not for lack of ideas that the US finds itself in its current predicament, a brilliant but declining superpower hobbled by entirely self-inflicted wounds. John Rawls, perhaps the most influential political philosopher of the 20th century, laid out some basic ideas, broadly known by the term “justice as fairness”. He describes a methodology by which we can objectively find how society should be organized. His principles are classic Western liberal ones of freedom and equality. We might think these are coherent with our foundational principles but in fact the US has diverged significantly from them, a subject we can discuss another time. For now let’s turn to Rawls’ philosophy.

Rawls asks us to formulate an “original position”, a foundational set of ideas from which the details of governance flow. To do this he proposes a thought experiment in which a “veil of ignorance” is placed over designers so they don’t know their place in society. They don’t know what race they are, gender, economic status, intelligence, ability, etc. Rawls argues that their original position will then favor a system of basic rights shared by all equally. These are pretty much the ones we have in liberal Western societies: the right to free expression, freedom of conscience, religion, etc. It would be irrational for someone ignorant of their future situation to favor any one type of person or to disfavor another. Equality and basic freedom is the only rational outcome.

Any new voluntary society will be faced with just this question. Its prospective members may have an understanding of their status in current society but they will not know to what extent they will have the same status in the new society. It is hopefully enough of a veil of ignorance that we can conduct the Rawlsian experiment. They will be asked to design foundational principles for their community that will probably gravitate toward the ones Rawls himself proposed. The important thing here is that the “original position” experiment is conducted before anyone has found “their place” in the new community.

Rawls also understood the notion of public vs. private views. He held that everyone has private views (eg religion) and that these views cannot be used as the basis for societal design. He argues that only public views, which are agreed to by everyone, can be used. He puts forth the concept of a “reasonable” person who has a civic obligation to argue for a position only from publicly accepted principles. This means, for example, that we couldn’t argue for limiting gender affirming treatment for trans youth on religious grounds but we can on the basis of child welfare. Rawls presumes that scientific information lies in the public sphere and is, therefore, acceptable as a public view.

He further posits that individuals will reconcile their public views with their private ones but that this process is necessarily different for every person. Therefore, no one needs to give up private religious beliefs to accommodate public principles. Reasonable people will make this reconciliation. Indeed they must if they are to live harmoniously in a diverse community. It will be important that foundational doctrines in ratings-based societies understand this idea.

Failure to do so, according to Rawls, is of course possible but leads to an unstable society, one filled with personal partisanship from the beginning. This should ring true to contemporary Americans. If durable communities are the goal, then heeding the Rawlsian concept of reasonableness will make sense. It would seem that our community-building efforts should include a healthy dose of education in political philosophy. Indeed, such an education should be open to the public, free, and required. A ratings-based society will have the means to determine how best to disseminate civic education.

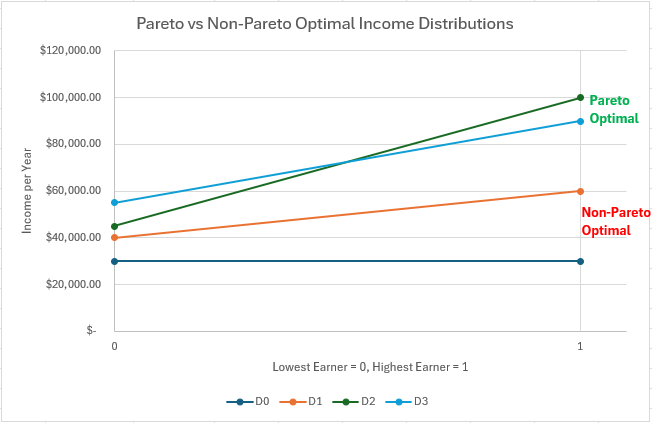

Another of his ideas is the “difference principle” which states that, to the extent that we have economic inequality, it should work to the benefit of the least advantaged. That is, economic inequality can exist but whatever wealth distribution it corresponds to needs to be better for the least advantaged than any other distribution. For example if the poorest members of a capitalist society earn $20,000 per year in a society where the wealthiest earn $100,000 per year, this would be preferable to a socialist society where everyone earns $15,000 per year. In other words, we tolerate wealth disparity as long as it helps the poorest members.

This idea fits nicely into an objective function. In this case we would seek to maximize the income of the poorest segment of society (say the lowest quartile) as a function of total societal income and the slope of the income distribution. Perhaps we could come up with a mathematical economic model to help us, but ultimately we’d want to use real economic data to find the optimum. Our community would try several distributions over time to find the one that maximizes the objective.

There are two problems with this particular objective function. One is that it requires a lot of learning over time. And the other is that reasonable communities may choose a more equal distribution of wealth even if it disadvantages the least fortunate. This is particularly true in post-scarcity societies that have the means to take care of everyone. Once everyone has a reasonable standard of living, does it make sense to allow vast wealth disparity for the sake of a little more, even if that little more also benefits the low end? Communities may decide that economic equality is a good in itself and choose it once post-scarcity conditions have been met. In short, communities may choose something besides Rawles’ economic objective function and still follow his concepts of liberal equality and freedom.

Rawls Redux

Here I’d like to expand a little on John Rawls and his philosophy of “justice as fairness”. Rawls is considered the greatest political philosopher of the 20th century, on a par with Hobbes and Locke, but is relatively unknown outside university philosophy departments. He’s received some attention of late, particularly in a new book, Free and Equal by the English economist/philosopher Daniel Chandler. A review of this book appeared recently in the NYTimes, giving it some cachet and perhaps breathing some new life into Rawls himself.

Rawlsian ideas never had much impact partially because John Rawls himself was a shy person and stayed out of the public spotlight. Also the world was beginning to move in a completely different direction at the time, with Reaganism and Thatcherism coming up and giving us a “neoliberalism” which placed individualistic capitalism at the forefront. Also Rawls himself did not give us a concrete implementation framework for his ideas, preferring to relegate it to more practical social scientists (as opposed to philosophers).

Chandler’s book is an attempt to revive Rawlsian thought, explain it to laypeople, and turn it into a prescription for practical ideas and political action. Many academics who write ground-breaking work like Rawls’ A Theory of Justice, tend to be ignored by the rest of society because their stuff is just too hard to read. Often, another writer (or the original author himself) will provide a more readable version and expand on the ideas. This is what Chandler’s book is.

We take up Rawls because it turns out many of his ideas fit in well with the ones we’ve been discussing regarding a ratings-based society. In doing this we will relate Rawls to other philosophies (eg utilitarianism, libertarianism, etc) and some discussions we’ve had on fraught topics, like privacy.

Rawlsianism has the benefit of being readily acceptable to large numbers of people, especially Westerners. Its tenet of basic liberties is largely familiar to us. His principle of equality and the “difference principle” is also familiar to us in general, even though it isn’t practiced in any sort of rigorous fashion. And similarly, the just savings principle, especially in relation to preserving the planet for future generations, is also a widely shared idea even though it remains politically controversial. But regardless of their political affiliation, no one in the west thinks of Rawls like they do Marx, for instance. His views are not fringe and, at least on the surface, seem almost banal. Hopefully this property will prove to be an advantage in planning a revolution.

Rawls in Summary

First, let’s summarize Rawls’ philosophy. He defines three basic principles along with a few sub-principles:

The Basic Liberties principle. These are personal liberties such as free speech, thought, religion, and basic political liberties such as the right to vote, assemble, and organize political parties. This principle is what put Rawls’ philosophy squarely in the liberal camp.

The Equality principle. This comprises two sub-principles, the first being equality of opportunity and the second being the “difference principle”. Equality of opportunity is about giving everyone the same fair chance to develop themselves. In it, we mostly give people the tools to develop themselves, such as education and employment chances that are free of discrimination. Most advanced democratic nations agree with this principle and practice it to some extent. But there is a large difference between our lip-service agreement with this idea and what we’ve actually accomplished. The difference principle is that we organize our economy to benefit everyone and, in particular, the least well off. Specifically, we allow inequality to the extent that it results in the best system for the least well off. This notion, at least in general, will also generate wide agreement in western democratic societies. But its implementation is very spotty. More on this idea later.

The “just savings” principle. This is also known as intergenerational justice or sustainability. The idea, as expressed by Rawls, is that we save enough so that future generations can also enjoy the freedom and material benefits that we have. Obviously, in our time, it also means not destroying the planet so future generations can live on it. Rawls believed that intergenerational justice compels us to treat future generations as we’d have wanted past generations to treat us. Needless to say, although this idea has certainly seeped into western thought due primarily to climate change, it has not had much of an effect. The hope, in the west, is that technology and market forces will conspire virtuously to save us from any difficult changes to our way of life.

Here we will look at each of these basic principles and relate them to our ratings system and some of our past discussions. We will see how Rawls’ three basic principles form a coherent whole. We will also discuss his views in comparison to some other political philosophies, namely neoliberalism, libertarianism, and utilitarianism.

The Basic Liberties Principle

Let’s first look at the Basic Liberties principle. How does one establish basic liberties? Rawls recommends a “veil of ignorance” in which we imagine ourselves to be ignorant of our future selves in a presumed new society: we wouldn’t know our level of wealth, our gender, job, race, religion, etc. We wouldn’t know what, if anything, we were good at, if we were intelligent, strong, or beautiful. Rawls believed that the veil of ignorance compels us inexorably to a set of basic rights for everyone because no one would want to end up in a disadvantaged position. It’s kind of like cutting a cake with your partner. You cut, she chooses the first slice. Your motivation is to make a very fair cut because you don’t know which slice you’ll get (presumably the smaller one if you mess up). In the same way, we would, behind the veil of ignorance, establish rights that were equal for everyone and prevented anyone from gaining undue advantage over us.

Some people question how a veil of ignorance is even possible. But according to Rawls, it isn’t through a deep state of self-abnegation that we achieve it. We do it through debate. Other people are on hand to let us know if we are really following the ignorance guideline or are letting biases seep in. Our ratings system is an obvious tool that can help in this regard.

If our goal is to settle on a set of basic rights, a constitution let’s say, then a rated debate about what those rights should be is in order. The debate will also inform the voting that takes place later to officially codify the basic rights. Ratings will ensure that the process is kept honest. So here we can relate Rawls directly to the ratings and debate system we have in mind.

The Equality Principle

In terms of the Pareto optimal wealth distribution developed earlier, we can apply the influence of Rawls as follows. Rawls believed that the economic system should benefit everyone, so we would choose a wealth distribution that is non-dominated (ie along the Pareto frontier). Within the scope of non-dominated points, however, Rawls would pick the one that maximized the benefit of the least well off, which in this case is the light blue curve.

Why the emphasis on the least well off? One reason is that we are trying to get to a society that is viewed by all its members as fair. If all economic systems are worse for the least well off than the one we have chosen, then there’s a reasonable expectation that the poorest members of society will think it is fair. This is in spite of the possibility that there would still be a distribution of income, with them at the bottom. In any case, if they believe it is fair, we might reason that anyone better off would also think of it as fair. Those better off who question this arrangement might be reminded that any other distribution, including those that benefit them, will do so only at the expense of the poor.

Rawls thus tolerated inequality, under these conditions. His idea for why some inequality might be better than none is the standard one: higher incomes provide an incentive for people to gain skills, work hard, and make valuable contributions to society. In other words, he believed in a society of merit, but not one where a meritocracy dominates through wealth and influence. He would reject the “meritocracy” we have today.

Reciprocity is one of the keys to Rawls. The guy at the bottom knows the guy at the top is being generous. The guy at the top realizes that his higher income is only possible because the guy at the bottom agrees that he deserves it. The guy at the bottom realizes he’s doing the best he can and society is doing the best it can for him. The guy at the top realizes that he can only do better by making the guy at the bottom worse. Reciprocity keeps society bound to each other in a system of mutual benefit.

The Just Savings Principle

Given Rawls’ first two principles, it isn’t hard to see that he would be quite motivated to secure the well-being of generations to come. His basic view is that we should treat the generation of the future as we would have wanted the previous one to treat us. A generation of hoarders which leaves little for the future is somewhat like an aristocratic class of wealthy people who leave little for the common people.

Rawls’ difference principle comes into play here as well. Clearly, if we are going to set up an economy that is optimized for the least advantaged, we would also set it up not to disadvantage people who haven’t yet been born. There is a system of intergenerational fairness over time that constrains our impulse toward material accumulation.

When Rawls wrote, people were aware of the environmental effects of industrial societies and, particularly, the effects of resource depletion. Think Limits to Growth. But they weren’t as aware of climate change as we know it today. Apparently their arguments turned out to be quite prescient.

The Just Savings principle is a clear-cut example which makes the case for ratings. It is very difficult for westerners to adopt self-sacrificing modes of behavior when everyone else isn’t. And it is, as we’ve discussed before, extremely difficult to engage in solo acts of criticism. In our case, we have societal values that we supposedly ascribe to but then don’t follow through in our personal behavior. The ratings system should point this out and make clear that those who succeed in closing that gap will do better. The ratings system should be especially geared toward issues of major long-term impact, like climate change. As a matter of community consensus, it is likely that we will agree on principles like Just Savings and design ratings that are appropriate for it.

How would this work? If we design ratings for, say, “environmental stewardship” we might all start off fairly low since we all tend to drive carbon-emitting cars and overuse our air conditioners. But if society placed a high enough weight on this particular rating, given its importance to future generations, making a change here would affect someone’s aggregate rating quite a bit more than other changes would. This is exactly how it should work. The ratings system has a realistic chance at achieving this and incentivizing the correct behavior.

Rawls and... Neoliberalism, Libertarianism, and Utilitarianism

Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism is the economic shift toward free-market capitalism that characterized economic policies starting in the 1980’s in the western democracies and continuing until today. Daniel Chandler singles out neoliberalism for special criticism in his book, Free and Equal. He sees it as a main contributor toward the vast economic inequality we have today. Rawls himself only saw neoliberalism in his later years when it became clear that the US and Britain had turned decisively toward it.

Daniel Chandler isn’t the only writer who has criticized neoliberalism. To give just one example, Joseph Stiglitz wrote a piece recently for the Washington Post about how neoliberalism needs to end:

Let’s take a moment and look at recent US history, in particular. The early 1980’s saw a shift away from traditional liberalism to neoliberalism with the election of Reagan in the US and Thatcher in the UK. Traditional liberalism was generally more Rawlsian, emphasizing both individual rights and fair wealth distribution. The US, by the 1980’s, had just finished a 30 year run marked by great progress in traditional liberalism.

Neoliberalism is marked by a focus on markets and individualism. Globalization was one result, displacing millions of middle-class workers in the US and, to a lesser extent, Europe. The 1990’s saw the election of Bill Clinton who continued in the neoliberal tradition and furthered globalization with treaties such as NAFTA and financial deregulation.

It took time for the excesses of neoliberalism to manifest themselves. Neither the Fed nor the President, both run by firm neoliberals (Alan Greenspan and George W. Bush) failed to anticipate or prevent the 2007-2008 financial crisis. The aftermath of this was a huge number of skilled working class jobs permanently lost, along with further globalization.

The long term consequences of neoliberalism were now clear: rising economic and political inequality. The US now rivals many third-world countries in its level of economic inequality. People are more disillusioned with their leadership than ever.

And neoliberalism was not our only policy failure (a bipartisan one at that). The early decades of the 21st century saw a resurgence of US military adventurism in Iraq and Afghanistan, the latter resulting in complete failure and the former in almost-complete failure. Obviously, disillusionment with US political leaders only grew.

One consequence of all this was political extremism on both the right and left. We proceeded, for example, to botch our response to the Covid pandemic (which killed 1.1 million Americans). The ineptitude of the government’s response was the result of years of reigning in the liberal regulatory state, another consequence of neoliberalism. This left public health agencies without the power or tools to do the job. It would seem that as a polity, the US is beginning to fail and neoliberalism is arguably at the root of it.

It appears that even though political scientists, economists, and philosophers have dismantled neoliberalism we have not, as a society, done the same. This is strange, and gives credence to the notion of a propaganda machine whose goal is to maintain the status-quo for the privileged. Even the prospect of ecological destruction, through global warming, is having relatively little effect on our politics.

Libertarianism

If neoliberalism is a rightward step from liberalism, then libertarianism is a rightward long jump. Needless to say, Rawls objected to libertarian conceptions of society. He felt that government was a key player in securing rights, creating conditions of economic fairness and intergenerational responsibility.

We have argued before that we all have a libertarian within us, to one degree or another. Even Rawls’ ideas of basic liberties can be viewed in a libertarian light. None of us likes the government telling us what to do, especially in what we consider strictly personal affairs. And despite an ever more extreme right, we have made some recent “libertarian” strides. We’ve legalized gay marriage and advanced LGBTQ+ awareness considerably.

But libertarianism seems to end where it begins as a political philosophy. It would be nice if it worked. If all we needed to do was get the government out of our way to ensure our rights, justice, and fairness, then the solution is simple. But there is no serious evidence that this would work. Societies where the government is weak tend to produce a kind of private tyranny no one in a western democracy would want to live under. The American libertarian vision of a harmonious society of private contracts, and extremely limited government, is simply nowhere to be found.

Let’s look at the most democratic countries, the ones that best ensure protection of rights, political freedoms, fairness, etc. We can look at the Freedom House’s map and take the ones at the top. These are not libertarian nations. They are societies that, over time, have designed a system of rights and wealth distribution. For whatever reason they have succeeded, relative to other countries. Theirs is a process that involves the government as a central player in the affairs of society, not one that minimizes it. Freedom apparently needs to be enforced, contradictory though that seems.

Incidentally, the US has also built government policies and systems to strengthen freedom but, unfortunately, it does not rank among the top tier of countries. We might note, however, that no country in the world approaches the Rawlsian ideal.

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism, a philosophy which has had a huge effect on Western thought, holds that our actions should be to the greatest aggregate benefit of everyone. It is considered to have been founded by the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham in the 1700’s, although earlier writers espoused similar ideas and its roots go back to antiquity.

Utilitarianism is an offshoot of consequentialism, the view that only consequences of actions matter. Their motivations or why they are undertaken is not important. A good description of utilitarian philosophy and history can be found here:

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/utilitarianism-history/

John Rawls had serious problems with utilitarianism. Perhaps the most serious is its tendency to sacrifice the few for the many. Utilitarianism is a numbers game. If the total aggregate good is maximized by penalizing a few people, utilitarianism holds that that was the correct choice. In utilitarianism, happiness, among other things, should be one of the goods produced by society, as long as we view it as total happiness. Therefore, policies such as the internment of Japanese-Americans during WWII to placate white Americans who were suspicious of them, could be justified. As we know, Rawls counters this possibility from the outset, by first describing a system of basic rights such that policies of this kind could not be undertaken.

Utilitarianism has other problems according to Rawls. It tends to treat people as interchangeable since they are merely the producers of “utilities”. Rawls instead defends the notion of individuality and holds that comparing utilities across persons is generally impossible since everyone is different. Another problem is that utilitarianism requires of people that they take actions consistent with aggregate good rather than personal good. Rawls thought this was an unrealistic demand to place on individuals. Rawls instead views society at large as the upholder of aggregate ideals, not individuals acting against their own self-interest. In this sense, Rawlsian morality is a social morality, not an individual one.

This is not to say that utilitarianism died with Rawls. We can certainly think of cases where individuals make sacrifices for the common good. But it is not, according to Rawls, a coherent way to organize society day to day.

Rawls and Privacy

Rawls does not directly address the issue of privacy rights but we can infer that he would believe in a right to privacy as part of his basic liberties principle. If we go behind the veil of ignorance, and consider what our basic liberties should be, most of us would reasonably include a personal right to privacy. This means the government, and others, cannot snoop on our private conversations, see us on camera while we’re in our homes, etc. It’s not a stretch to think that Rawls would agree.

Generally speaking, Rawls considers rights basic if they are required to advance someone’s moral powers, develop a sense of justice, or pursue a conception of the good. To do so we might be expected to develop a strong sense of identity and relationships with others. Importantly, we might also need to make decisions that were free from interference or surveillance by others. It would appear that privacy is a basic raw material in any reasonable concept of personal liberty.

But how far this goes might be subject to some debate. Let’s take the case of strong encryption and whether it should be considered a part of our basic right to privacy. Usually we associate this technology with the ability to hold a private in-person conversation in a room with no one else listening. This is not controversial and practically every Western person believes in such a right. Encryption simply gives us the ability to do this across the internet. It would appear that this technology is in keeping with a Rawlsian right to privacy.

We might pause, however, if we started seeing sufficient crime or terrorist activity enabled by encryption. Clearly, society has to determine where the balance is. Is it just a couple of minor incidents a year or is someone setting off dirty bombs in major cities? Any fundamental right to privacy that has a direct consequence of endangering our physical person (another fundamental right) would be subject to review.

This is in keeping with a Rawlsian notion of practicality and balance. A basic right exists up to the point where it interferes with another basic right. Clearly our basic liberties include the right to feel safe in our private and public spaces. An undue interference with that resulting from another basic right might necessitate some limitations.

In a nod toward utilitarian consequentialism, I would add to Rawls by proposing that rights are subject to results. People have the right, presumably, to play violent video games. If everyone understands that it’s just a game and their real-world behavior doesn’t change, it’s not a problem. But if everyone who played such a game turned into a mass shooter we might think twice about this particular right. Incidentally, there was a Star Trek TNG episode called “The Game” where a video game of sorts addicted the Enterprise crew in an attempt by an alien power to take over the Federation. Beyond its entertainment value, the point of the show was to comment on this topic. Consequences obviously matter.

We might further observe that, from our original position, the default is probably for a right to exist. We wouldn’t know in advance which rights might result in danger since we don’t have a good understanding of ourselves in such a condition, let alone an understanding of others or society at large. In other words, the default position is to grant the right. It is only in reaction to subsequent consequences that we would contemplate removing it.

In a conversation with Lem, he expressed a concern about the ability for people to dissent and revolt and that without privacy, they wouldn’t be able to do so. Clearly encryption furthers the ability for dissenters to communicate. And governments will always use personal safety as an excuse to crack down on encryption. In a free society we have the ability to change the government’s policy on questions like these, as long as we are aware of what is going on.

The Patriot Act, passed in the wake of 9/11, is an example of this. It allowed the government to detain suspected terrorists and eavesdrop on electronic communications with much greater ease than previously. It was reauthorized several times until 2020 when it expired. Over the years of its life, it gained notoriety due to the government’s bulk collection of private communications and the lack of due process for terrorism suspects. It should be noted that, although expired, federal intelligence and law enforcement personnel still have many of the powers granted by the act.

This is a fact which is not clear to most people. Among the minority that have any understanding of this issue at all, most believe the Patriot Act to either be expired, which it technically is, or to believe that it has been reauthorized in perpetuity. The truth lies somewhere in between. A basic understanding of this point would be crucial for further discussion in American society. Instead, we have a system where the majority don’t participate and are simply unaware. Indeed, the act was passed, like the decision to go to war in Iraq and Afghanistan, in a frenzy of panic over 9/11. Needless to say, this is not the deliberative process favored by Rawls, which carefully balances basic liberties and fairness.

Chandler's Solutions

Chandler’s purpose is to pick up where Rawls left off and create a practical agenda for change. Chandler points to political parties and the news media as key intermediaries in producing the political conditions for change. He clearly identifies himself with progressive politics. Some of his solutions include:

- Remove the influence of money in politics. Studies have shown that once the views of the rich are taken into account, the influence of the average citizen on real policymaking is nill.

- Eliminate winner take all with a proportional representation system.

- Automatic voter registration.

- Elections on weekends.

- Universal basic income.

- Publicly funded media as a contrast to the profit-driven model.

- Establishing more mechanisms of direct democracy such as a Brazilian model of participatory budgeting.

- Voting voucher system – Everyone gets a fixed amt. of money to spend on supporting candidates.

- Universal basic inheritance – Every 18 yr. old is given, say $100,000 funded through progressive taxation.

- Co-management of companies (like they do in Germany) where workers have a certain number of board seats. He argues that companies do quite well under this system.

- Creating fairness in the distribution of wealth in our public schools. The system in the US is based mostly on property taxes which allows for “rich” schools and “poor” schools.

- Strengthening civic education in our public schools. Chandler contends that education in civics has been pushed out as a priority in favor of marketable skills (eg STEM).

- Service learning in public schools.

- Compulsory national citizens service.

And so it goes, with many more specific ideas. Most of these ideas are well known, however, and this is the part of Chandler’s book where it gets difficult to see what is being offered that is truly new. But he doesn’t offer anything new to start with. His book is an attempt to take an old, or middle-aged, idea and revive it. That he marries it with modern progressive policy ideas is to be expected.

Chandler’s political prescription is for progressive parties to move beyond triangulation and focus groups and to, instead, make a fundamentally moral argument. He further asks how we can become producers of democracy rather than simply consumers of it. Obviously, education is part of it and many of his other ideas are attempts in this direction (eg compulsory civil service). Clearly, our system, based on ratings will build participation in from the outset and use more of a direct-democracy approach.

Incidentally, Dan proposed a voting mechanism in the community based system where the individual gives part of their weight to someone else for ratings. For example if Joe doesn’t have any medical knowledge he might delegate his weight to Mike, who is a doctor. The doctors would then have more power to vote and rate on medical issues. This mechanism strikes me as inherently Rawlsian since it allows, purely through consent, a more optimal distribution of power, one that is better for everyone.