More actions

Created page with "Productivity is normally defined as output per worker per hour. It is the central measure of economic progress in any society and the basis for increased standard of living (at least in material terms). The following graph shows how US productivity has increased since 1947, the first year the Bureau of Labor Statistics started tracking it. image Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/productivity Also: ht..." |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

But the subjective notion of value in a moneyless economy is certainly a step in the creation of money and shows just how natural the concept of money is. But we could remain determined not to introduce money and simply use the productivity numbers for statistical purposes. This is useful, even with no formal market mechanism behind it. |

But the subjective notion of value in a moneyless economy is certainly a step in the creation of money and shows just how natural the concept of money is. But we could remain determined not to introduce money and simply use the productivity numbers for statistical purposes. This is useful, even with no formal market mechanism behind it. |

||

If there is no market-basis for value, how would we assign prices? The answer is that we wouldn’t. In a moneyless society goods and services are distributed based on need first and ratings second, as [[ |

If there is no market-basis for value, how would we assign prices? The answer is that we wouldn’t. In a moneyless society goods and services are distributed based on need first and ratings second, as [[A moneyless economy based on reputation and need|we have discussed]]. A pricing mechanism is basically a voting system and our proposed economy would simply not have that particular one. |

||

By the way, we could also do this in a moneyed economy. There is no economic law that says pricing is determined by what people are willing to pay. Goods and services would exist and would be distributed according to need and ratings. We could simply assign prices to the goods depending on how difficult they were to manufacture (ie computers are more valuable than can openers) and use those prices to calculate productivity. If someone were to order a new product and win the claim to it, they could simply be given the money to “buy” it. Or the money transfer, such as it were, could be handled automatically from the “bank” to the firm. Again, we may choose to have money to perform statistical tasks but not use it as a scarce resource or a price voting mechanism. |

By the way, we could also do this in a moneyed economy. There is no economic law that says pricing is determined by what people are willing to pay. Goods and services would exist and would be distributed according to need and ratings. We could simply assign prices to the goods depending on how difficult they were to manufacture (ie computers are more valuable than can openers) and use those prices to calculate productivity. If someone were to order a new product and win the claim to it, they could simply be given the money to “buy” it. Or the money transfer, such as it were, could be handled automatically from the “bank” to the firm. Again, we may choose to have money to perform statistical tasks but not use it as a scarce resource or a price voting mechanism. |

||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

We could also choose a middle term approach where money is not used for most things but is used for luxury items. Since we advocate a system in which everyone receives a minimum basket of needs, and we assume the post-scarcity condition of an industrialized western nation, this basket can just be handed out to people. There wouldn’t need to be any money. This is akin to the way certain services are already provided, such as public K-12 education. Beyond that, we would distribute most other goods based on ratings. But we could have a category of scarce luxury items that do require money, in order to ascertain their price and match them with demand. We wouldn’t want our society to devote itself inordinately to the manufacture of luxury items but it may be motivational for some people to have access to them. The money, therefore, can be distributed based on ratings and limited based on how many luxury items the [[community]] wanted to produce (presumably, not much). |

We could also choose a middle term approach where money is not used for most things but is used for luxury items. Since we advocate a system in which everyone receives a minimum basket of needs, and we assume the post-scarcity condition of an industrialized western nation, this basket can just be handed out to people. There wouldn’t need to be any money. This is akin to the way certain services are already provided, such as public K-12 education. Beyond that, we would distribute most other goods based on ratings. But we could have a category of scarce luxury items that do require money, in order to ascertain their price and match them with demand. We wouldn’t want our society to devote itself inordinately to the manufacture of luxury items but it may be motivational for some people to have access to them. The money, therefore, can be distributed based on ratings and limited based on how many luxury items the [[community]] wanted to produce (presumably, not much). |

||

Note that in most cases cited here, we have rejected money and market-based price judgements. We emphasize that this does not detract from our ability to measure productivity and use it as an important objective function in societal optimization. |

Note that in most cases cited here, we have rejected money and market-based price judgements. We emphasize that this does not detract from our ability to measure productivity and use it as an important objective function in [[societal optimization]]. |

||

Revision as of 19:41, 26 September 2024

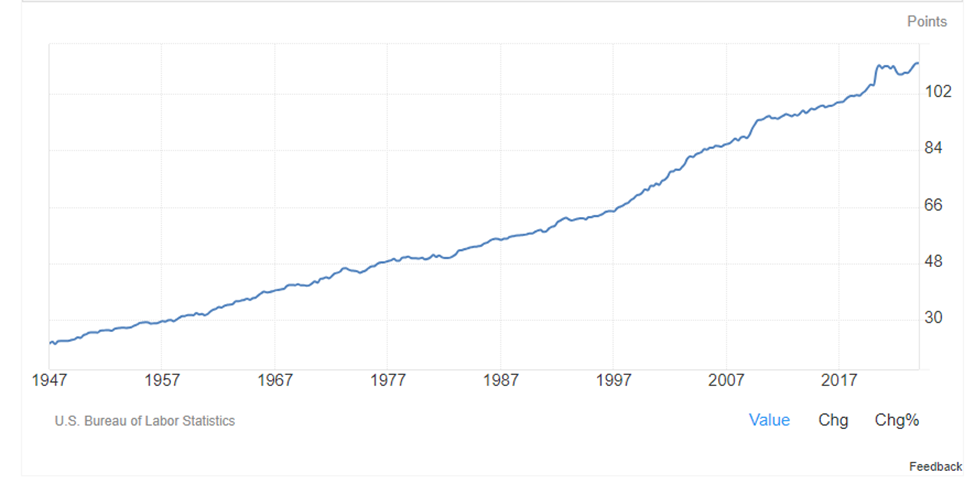

Productivity is normally defined as output per worker per hour. It is the central measure of economic progress in any society and the basis for increased standard of living (at least in material terms). The following graph shows how US productivity has increased since 1947, the first year the Bureau of Labor Statistics started tracking it.

Source: https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/productivity

Also: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/OPHNFB

To the question of whether this is based on real GDP (ie inflation adjusted) or not, the answer is yes. GDP over years of time is normally plotted after adjusting for inflation since inflation would be too much of a confounding factor (our inflation since 1947 is a factor of 13). According to the source above, “Labor productivity is calculated by dividing an index of real output by an index of hours worked of all persons…”

As we can see, productivity in the US is about 5 times higher today than it was in 1947. The first thing to ask about numbers like these is whether they make sense. Do they pass a basic smell test? This is often a critique of US vs. European standards of living. Proponents of US style laissez faire capitalism will point to the social democracies in Europe and declare that we are doing much better than they are based on GDP per capita. But a passing visit to any of the countries in question reveals that their people live just fine. Some things are better, some worse, but on balance middle class people in both areas are at a rough parity.

So would a subjective dive into your likely 1947 life make you conclude that your standard of living was 5 times lower then? This is hard to quantify but it seems within the ballpark. There was substantially less food, medical knowledge was drastically lower (no antibiotics), entertainment/information was limited to radio, print publications, and the occasional movie (in a theater), you may have had a telephone in your house (which everyone shared), educational opportunities for most were limited to high school, at best (the GI bill was just getting started which made college a viable option for the masses). The level of human services was also diminished. Mom’s pretty much raised their kids themselves. Airplanes were not yet a mainstream mode of travel. Cars were not as ubiquitous and more people used public transit. More people lived where they grew up. More people did physical labor for their jobs. Buildings were not air conditioned or heated as well. Life was quite a bit harder and more uncomfortable. But we still had many of the benefits of modern life. A factor of 5 seems reasonable.

How would we measure productivity in a ratings-based society? Obviously we could have a rating for productivity which would give us a subjective view of each person’s contributions. But we would probably want a more direct objective measure as well. Although the factor of 5 seems reasonable, it’s not at all clear that we would have arrived at that prior to seeing the numbers.

In a moneyed society we would use the value of what everyone produces. This is hard to break down to an individual level but for a company, for instance, it might result in dividing its revenue by its employees and then differentiating between the employees in some manner that adds up to the total. The differentiation would be subjective for employees that don’t have clear output metrics (eg managers) but could be objective for those who do (eg line workers). In an economic system with no companies, we could perform this same exercise at the community level.

Here we create a baseline productivity () by taking the total production of the firm () and dividing it by the total hours worked ().

If we then assign this number to each individual and multiply by their hours worked we would obtain the total production. here is hours worked for each individual:

We will assume that hours worked is objectively measurable through clock-in/out procedures or timesheets. If we then multiply this by a subjective productivity rating for each individual (), we obtain a total production which is less than the actual total production (because the ratings are 0-1). We call it the total baseline production ():

So we introduce a normalization factor () which is simply the actual total production divided by this number.

This factor ensures that the sum of individual productivities always adds up to the actual total productivity:

In a moneyless society, we could do something similar if we were willing to take the step of assigning numerical values to production. This would be subjective but keep in mind that subjective judgements of value are ultimately how the moneyed economy works too. People make judgements, subjective ones, and assign prices to things based on them. For instance, the price of luxury cars would drop to the price people were willing to pay if we all decided they weren’t worth that much. A moneyless value assignation scheme is only different in that we wouldn’t also have a market pricing mechanism.

But the subjective notion of value in a moneyless economy is certainly a step in the creation of money and shows just how natural the concept of money is. But we could remain determined not to introduce money and simply use the productivity numbers for statistical purposes. This is useful, even with no formal market mechanism behind it.

If there is no market-basis for value, how would we assign prices? The answer is that we wouldn’t. In a moneyless society goods and services are distributed based on need first and ratings second, as we have discussed. A pricing mechanism is basically a voting system and our proposed economy would simply not have that particular one.

By the way, we could also do this in a moneyed economy. There is no economic law that says pricing is determined by what people are willing to pay. Goods and services would exist and would be distributed according to need and ratings. We could simply assign prices to the goods depending on how difficult they were to manufacture (ie computers are more valuable than can openers) and use those prices to calculate productivity. If someone were to order a new product and win the claim to it, they could simply be given the money to “buy” it. Or the money transfer, such as it were, could be handled automatically from the “bank” to the firm. Again, we may choose to have money to perform statistical tasks but not use it as a scarce resource or a price voting mechanism.

We could also choose a middle term approach where money is not used for most things but is used for luxury items. Since we advocate a system in which everyone receives a minimum basket of needs, and we assume the post-scarcity condition of an industrialized western nation, this basket can just be handed out to people. There wouldn’t need to be any money. This is akin to the way certain services are already provided, such as public K-12 education. Beyond that, we would distribute most other goods based on ratings. But we could have a category of scarce luxury items that do require money, in order to ascertain their price and match them with demand. We wouldn’t want our society to devote itself inordinately to the manufacture of luxury items but it may be motivational for some people to have access to them. The money, therefore, can be distributed based on ratings and limited based on how many luxury items the community wanted to produce (presumably, not much).

Note that in most cases cited here, we have rejected money and market-based price judgements. We emphasize that this does not detract from our ability to measure productivity and use it as an important objective function in societal optimization.